Structural reforms and science and technology policies in Argentina and Brazil

Fabio S. Erber, Texto preparado para o Seminário “Políticas para fortalecer el Sistema Nacional de Innovación: La experiencia internacional y el camino empreendido por la Argentina”, organizado pela Secretaria de Ciencia y Tecnologia, Buenos Aires, Setembro 1999.

Este artigo analisa as políticas de ciência e tecnologia (STP) na Argentina e no Brasil durante os anos noventa. Começa (seção 2) por uma breve excursão em torno do cenário em que tais políticas foram concebidas e executadas - a onda de reformas institucionais que engolfaram os dois países durante esse período. O principal objetivo dessa excursão é discutir as implicações das reformas para o desempenho das atividades de C & T (S & T), descritas na Seção 3. A próxima Seção discute as principais características do STP nos dois países - seus objetivos, instrumentos e resultados. A seção 5 discute as medidas de STP relacionadas ao MERCOSUL. As seções 2 a 5 enfocam o presente e o passado recente. A última Seção apresenta as conclusões do artigo e lança um olhar cauteloso para o futuro.

1. Introduction

This paper analyses the science and technology policies (STP) in Argentina and Brazil during the nineties. It begins (section 2) by a brief excursion around the setting in which such policies were conceived and performed – the tidal wave of institutional reforms which engulfed the two countries during this period. The main aim of such excursion it to discuss the implications of the reforms for the performance of S&T activities (S&TA), described in Section 3. The next Section discusses the main features of the STP in the two countries – their objectives, instruments and results. Section 5 discusses MERCOSUL-related STP measures. Sections 2 to 5 focus on the present and the recent past. The last Section presents the conclusions of the paper and casts a wary eye to the future.

2. The Concept of Structural Reforms, S&TA and STP

Looking at the paths of development followed by Argentina and Brazil over the last fifteen years two strong features emerge: first, the degree of interdependence between the two economies; second the similarities, the parallelism which exists in the policies pursued in the countries. The first phenomenon is largely attributable to the bilateral agreements of the mid-eighties and more recently to the Assuncion Treaty which created the MERCOSUL. As a result of such policies, the two economies have become inextricably interdependent in terms of trade and investment, firms (especially transnational companies – TNC) look at the two countries as a single market and cultural ties have tightened. However, the integration of STP is very limited (as we shall argue in more detail later on) – in both countries STP retain a national focus. A possible explanation for this is that in the two countries STP are marginal to the structural reforms which have dominated their environment during the nineties. STP are weak swimmers in a strong tide – they can hardly support each other.

This argument brings to the fore the second feature mentioned above: the parallelism of structural reforms. The way in which the reforms were conceived and implemented strongly conditions the STP and the S&TA and it is by the reforms, by the environment of science and technology policies and activities, that the analysis should begin.

The origin of the reforms can be traced to the failure of the policies of the Alfonsin and Sarney governments during the mid-eighties to bring about economic stability and growth, coupled to a strong consensus between the international financial and industrial community and the governments of the main industrialised countries about what should be done in Latin America to produce stability and growth and, at the same time, support their stakes in the region. The Ten Commandments of the Washington Consensus are too well known to need repeating here (Williamson 1990), but it is worth recalling that the Consensus did not lay a blueprint for the sequencing of the reforms; neither was it clear about how growth would result from the reforms, except for a faith that, given the “right” institutions (“market-friendly”) the market mechanisms (national and international) would produce the desired result.

“Structural reforms” is an expression with deep emotional and political undertones and full of ambiguities. In the early sixties it was the banner of the left. In the nineties, it changed hands. Present-day evolutionary theories argue that development is the result of the co-evolution of two structures: productive and institutional. The theoretical underpinning of the reformers of the early nineties — traditional neo-classical economics enhanced by the new institutional economics and public choice theory — focused on institutions only. If the institutional structure was duly reformed, development would follow. The market and comparative advantages would look after the productive structure.

In the view of policy-makers, growth would result from a complex process in which two virtuous circles were entwined. The first circle was related to the process of globalisation (defined as the growth of trade and investment above the growth of production and the elimination of distinctions between foreign and national capitals). Trade and foreign direct investment (FDI) would introduce competitive pressure into the erstwhile protected markets and bring in more modern machinery and inputs, increasing productivity. Trade and FDI are closely related: FDI requires freedom to import but, at the same time, has a greater propensity to export. In the long run such investment would lead to increases in productivity and hence to greater exports. It did not matter that a considerable part of FDI was directed to purchasing local (private and State-owned) firms, since this was a prelude to increases in productivity and greater exports. Therefore, the large deficit in the transactions account of the balance of payments was a temporary phenomenon as was the reliance on short-term international finance to fill in the foreign exchange gap. By the same token the very high interest rates required to attract financial capital would be short-lived.

The second virtuous circle was related to the internal market. Here, trade liberalisation would lead to a progressive income distribution by acting as a brake on price increases by domestic producers and regional integration would enhance the domestic market further. Price stability would provide entrepreneurs with long term horizons. Privatisation and de-regulation would coalesce with imports and FDI to increase competition. Wider markets, positive expectations and greater competition would lead to new investments and trade liberalisation would allow the imports of new vintages of machinery and inputs and therefore to increases in productivity, exports and growth. Fiscal reform would support the decline of interest rates and more “flexible” labour legislation would reduce costs and increase international competitiveness. The adoption of an over-valued exchange rate strengthened the mechanisms of the two circles, linking further the stabilisation and growth components of the strategy.1

The establishment and operation of the two virtuous circles was fully entrusted to market mechanisms enhanced by State reform. If STP had a role, it would be found in the eventual failure of such mechanisms. But the very abundance of market failures poses a strategic problem: by which failure should STP begin? Welfare theory does not provide an answer to that question since in the presence of several failures and being impossible to remove them all simultaneously, there is no a priori Paretian criterion to distinguish between two imperfect positions (Nath 1969). External criteria deriving from other economic and political considerations must be introduced to select priorities, as Lall (1994) argued was done in Southeast Asia.

A possibility, adopted throughout the world, would be to establish sectoral priorities, since one of the main aims of STP is to support the change of the productive structure. Potato chips are not equal to computer chips: there are sectors which are more dynamic because they are more S&T-intensive and which supply the means of technological change to other sectors. According to their technical characteristics and the role they play in the process of creation and diffusion of technology different types of sectors require different policies. STP is necessarily differentiated by sectors (Erber 1992). But to the to the reformers of Latin America sector-specific policies where anathema, equated to “picking the winners”, no matter how strong the evidence that such policies had served well other newly-industrialised countries such South Korea and Taiwan2.

In other words, the concept of development by institutional reform adopted in the two countries implied that STP was limited to intervene only when the market failed and to do so by means of “horizontal” measures, designed to serve all sectors alike.

Although the view of development summarised above was shared by the policy-makers of the two countries, adherence to it was much stronger in Argentina than in Brazil – na indication that “history matters”. To take a few examples from the reforms: in Argentina trade liberalisation run faster and deeper, privatisation was quicker and included even the oil company, a symbol of national development.

The silence about differences among sectors was not complete ( the productive structure is like the naturel, chassez-le il revient au gallop!), especially in Brazil, which had the strongest tradition of sectoral policies. Although the Informatics Policy of the eighties was abhorred by the new policy-makers since it favoured local entrepreneurs and local technology (and was a bone of contention with the United States), it was replaced by special fiscal incentives to the sector (in fact, the electronics complex) and by a special programme to stimulate software exports, discussed below. The main development agency, the National Bank of Economic and Social Development (BNDES) reformed its structure to introduce departments responsible for sector studies, by the mid-nineties started specific programmes to support sectors most affected by import competition (e.g. shoes) and, more recently, has announced its intention to intervene in petrochemicals and steel in order to clear the imbroglios of crossed equity participation and size of enterprises resulting from the privatisation process. In 1999 the Government created a new Ministry for Development out of the old (and highly inefficient) Ministry of Industry and Trade and put BNDES under its jurisdiction. Ministry’s high officers are presently holding meetings to define sector policies

The social and economic pact which had produced in Brazil what Castro (1994) has aptly termed “the social convention for development” was resilient – sixty years of history could not be abolished by fiat. Although the pact had come asunder and lacked any strategic direction from the State its fragments still marched on under the guise of sector policies. Macroeconomic policymakers deprecated such measures but turned a blind eye on them. Nonetheless, even those within the Government who advocated a “policy for investment and competitiveness” (Mendonça de Barros and Goldenstein 1997) did not go as far as presenting a “vision” of the structure of the sectors in which intervention was introduced (justifiable to compensate the well-know market failures as regards myopia and co-ordination, as even the World Bank accepts) and, much less, a “vision” of the overall industrial structure. The latter authorities retained an ad-hoc view of sector policies – the State as fireman.

Even Argentina, where adherence to the reform orthodoxy was strongest, succumbed to temptation and introduced in 1991 a special regime for the automotive sector, based on import restrictions and export incentives, duly followed by Brazil three years later, with a significant difference: incentives for local purchases of capital goods, which did not exist in the Argentinean automotive regime. Such difference reflects not only the larger role of capital goods in Brazilian industrial structure but also a lasting commitment of Brazilian policy makers to industrialisation. Setting tariffs on machine-tools at zero level as Argentineans policy-makers did in 1992 was not politically feasible in Brazil, no matter what the macroeconomic planners said about the virtues of importing capital goods. Quite the contrary, FINAME, the subsidiary of BNDES in charge of financing purchases of equipment, expanded its operations.

Such differences are present in STP too. In Argentina laissez faire for S&TA prevailed until 1996, when the Secretary of Science and Technology resurrected from the ashes. In Brazil the Ministry of Science and Technology was for a while transformed into a Secretary attached to the Presidency but soon recovered its ministerial status and, no matter how limited its resources and power, it was taken for granted that a STP had to exist. It is also noteworthy that in Argentina the two official STP plans (GACTEC 1997, 1998) justify the policy by virtue of market failures, while in Brazil it is not felt that such justification is necessary.

Notwithstanding such deviations, in both countries the reform rhetoric and plans were adopted wholeheartedly by the macroeconomic policy-makers, which laid the ground rules whereby development should resume. In both of them the sequencing was similar, albeit with the differences in speed and force above mentioned: it begun by trade liberalisation, by the privatisation of State enterprises, elimination of legal differences between local and foreign capitals and by the reduction of State regulation (e.g. as regards foreign capital). Financial liberalisation and new institutions intended to increase competition (e.g. laws on intellectual property) followed, but State, fiscal and labour legislation reforms have not been completed to date. The latter provide ammunition for those who argue that the reform path has to be trod on.

Let us forget the failures of the market, suppose that the model had worked and high and sustained growth had been achieved and then examine the consequences for S&TA. To simplify, let us concentrate on S&TA of enterprises since the latter were, by definition, the main actor of the model. To do this it is useful to take a “portfolio” approach, whereby the firm is seen as a bundle of assets organised by routines and conventions which distributes its expenditures on new assets according their expected costs, revenues and uncertainties over time. According to such view, technological assets are just one of the many assets in which a firm may invest3. Moreover, technology assets are a portfolio by themselves, with different expected costs, revenues, uncertainties and timing. The structure of the latter portfolio defines the “technological strategy” of the firm.

The amount of investment a firm does in technological assets is conditioned by the technological opportunities and by the type of competition and user-producer relationships it faces in the sectors in which it operates, as well as by growth prospects, determined be macroeconomic conditions such as the rate of growth of the economy, the degree of international openness and income distribution. A crucial determinant of such investments is the national market for credit and capital, not only because it defines the availability of finance for technological assets but also because it defines the opportunity cost of technology investment (a feature normally overlooked in evolutionary analysis because it does not operate in the context of a “monetary economy” in the Keynesian sense)4. Obviously, the level of investment in technological assets is conditioned not only by macro and mesoeconomic factors: micro factors, such as the previous accumulation of technological assets and the routines and conventions attached to such history play an important role as does the ownership and size of the firm and its financial capability to increase debt and/or run risks.

Technological assets may suffer depletion in the same way (and probably faster) than physical assets – e.g. by closing down labs, disbanding engineering teams, but it is assumed here that a firm has to maintain a minimal level of expenditures on technological assets to remain in business (e.g. quality control and for minor product and process improvements). Such level is largely a consequence of the macro and mesoeconomic factors outlined above. Moreover, the increase in technological assets has also limits, given by a combination of meso and micro factors. In other words, firms invest in technology according to a floor and ceiling pattern.

Then, following the portfolio approach outlined above, what would have happened to the investment in technological assets had the reform growth strategy performed according to plan? A higher and sustainable rate of growth combined with an increase in competition stemming from trade and investment liberalisation and de-regulation would probably lead to higher investments in technology, reinforced by longer time horizons and lower interest rates and lower wage costs. The floor of the investment level in ST&A would probably be shifted upwards. At the same time, globalisation (trade and investment) would increase the time and competitive pressure on firms to use international process technologies and to supply products according with international standards. In other words, the idiosyncratic element of S&TA – the local element – would be discouraged in terms of uncertainty and revenue. Therefore imports of technology (embodied and disembodied) would become the most valuable asset in the technology portfolio. Although such imported assets require complementary local assets to be properly used (e.g. production engineering and detailed design skills) so as to adapt processes and products to local conditions, the local assets (many of which were already available in Argentina and Brazil as a consequence of the previous period of industrialisation) do not require a large deployment of resources and time to develop. Therefore the ceiling of the investment level would tend to be low.

A further linkage between the macroeconomic policies and S&TA may be found through the portfolio approach outlined here. Two main important features of the structural reforms were higher internal interest rates and lower exchange rates. Both lead to a preference for imported assets, especially in the cases of Argentina and Brazil where stability was “anchored” by an over-valued exchange rate and rates of interest were kept high to attract financial capital to fill in the current transactions account. Moreover, high interest rates tend to shift the composition of the overall portfolio towards financial assets and the structure of the technology portfolio towards investments in assets with relatively short periods of maturity. In other words, monetary and exchange policy tended to favour imports of technology and investments in local S&TA directed to changes in management organisation and adaptations of products and processes. In this context, firms having access to international sources of finance (i.e. with lower interest rates and longer maturity) were better placed to invest in local S&TA.

Given the macroeconomic strategy outlined above, the role of FDI in the definition of the ceiling of investments on technology is critical. First, international firms are supposed to set the pace at which the economy is growing and, therefore, the intensity of technological efforts. Second, more directly, by their size and connections international firms are better placed to carry out more ambitious technological programmes (if they are likely to carry them out is an issue discussed below). Third, they exert an important influence on the S&TA investments of their suppliers and customers, as well as of their local competitors. Fourth, FDI has transferred to foreign ownership some of the local firms which had developed significant technological assets, in the private sector (e.g. the leading auto parts producers) and privatised public companies (e.g. telecom). Finally, FDI dominates the sectors which are more technology-intensive within the productive structure of the two countries (especially in durable consumer goods and capital goods production).

Prima facie, it seems unlikely that firms which have easy access to technological assets already developed elsewhere (i.e. which represent sunk costs from the point of view of the group as whole) will replicate such investment under conditions where there are less economies of scale and scope and less externalities deriving from a long-established national system of innovation. Investments which would be necessary would be geared to adaptations of products and processes to specific local conditions, such as raw materials (e.g. producing pulp and paper based on short fibre eucalyptus) or income distribution (safety devices in autos). Under such circumstances, R&D facilities set up by the companies FDI purchased could become easily redundant.

Although the broad picture outlined above is consistent with S&TA conducted by international companies in Argentina and Brazil in the past, there are variants which may be important5. First, a considerable part of recent FDI was from firms already established in the two countries. The local subsidiaries of such companies have already developed some important technological assets in terms of engineering capabilities which may be used within the group, leading to an eventual upgrading of local S&TA. Second, MERCOSUL enlarged market in many cases led the international group to attribute greater responsibility to their subsidiaries in Brazil or Argentina, often extending to the rest of Latin America. Third, the trend towards “global” products, standardised urbi et orbi, coexists with the trend towards more regional approaches, where the accumulated technological assets of Brazilian and Argentinean subsidiaries may be important. Finally, not all acquisitions of local firms were in fields where the purchaser already had fully fledged technological assets – some had the objective of acquiring simultaneously market share and technological assets. In the latter case, one may expect an expansion of S&TA rather than its reduction.

Notwithstanding the nuances above painted, the overall picture of FDI S&TA seems to be one in which the level of technological investment is relatively low, designed mainly for adaptations of innovations produced elsewhere.

The role attributed to FDI in the overall growth strategy has another significant, stemming from denial rather than affirmation. An important determinant of STP in the past was the desire for greater national autonomy. Autonomy (or nationalism) evolved from the control of natural resources in the thirties to technological capabilities in the seventies and it was always associated with national enterprises, private and – quite often – State- controlled. In this view STP was a means for achieving autonomy and its legitimacy was a consequence of this functionality.

To sum up this old view, foreign firms would not transfer to their Latin American subsidiaries innovation capabilities, so national firms were the main actor for strengthening technological autonomy. However, market mechanisms tended to operate so as to reduce the technological capabilities of national firms to adaptation too. Therefore, State intervention was required to stimulate national enterprises to upgrade their technological programmes. Such intervention did not require failures of the market to be justified – national interest in terms of greater autonomy and (supposedly) entry in the new industries and services which warranted further development sufficed.

Such view played a much stronger and lasting role in Brazil than in Argentina and it may at least partially explain the different trajectories followed by STP in the two countries during the preceding decades.

It is beyond the scope of this paper to discuss the virtues and shortcomings of such view, but is important to point out that the prevailing view, which concentrates on the market, denies any significant difference between capitals of distinct origin and looks upon FDI as the carrier of modernity, completely reverses the rationale of the old STP. Whatever legitimacy it held in the past by its autonomy-enhancing properties is not only negated but militates against it, as a symbol of a past that should be forsook6.

3. Reforms and S&TA in Argentina and Brazil

The reform path followed by the two countries was similar. Trade and foreign investment were indeed liberalised. As foreseen, imports soared, but, alas, exports lagged behind, not only because commodities performed poorly in the international market but also because FDI (which did come in) had (as expected) high propensity to import, often disarraying whole productive chains, but did not conform to expectations as regards exports. This was in part due to the fact that a considerable part of FDI came in to buy local enterprises7, many of which, such as the public utilities, were engaged in non-tradable activities but also because most of the tradables-related FDI has the national markets as a focus, or, at best, the MERCOSUL enlarged market.

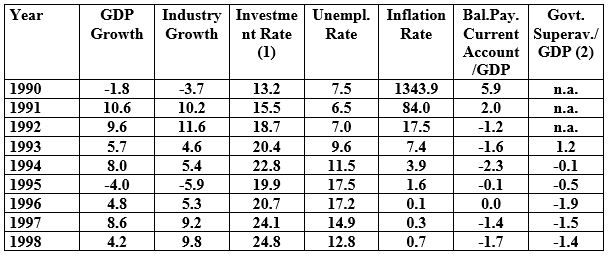

Let us consider some evidence. From many points of view Argentina could be taken as a show-case for the reforms. As shown in Table 1, albeit starting from very depressed levels, growth rates and investment were very high from the inception of the Plan de Convertibilidad (which pegged the peso to the dollar) until 1995, when the Mexican crisis took its toll. Nonetheless, the economy recovered fast, partly as a result of the over-valuation of the Brazilian currency, and achieved high growth rates in 1997. Growth rates plunged back in mid-1988 and in 1999 are negative, partly as a result of the drastic devaluation of the Brazilian currency early this year.

Brazil started reforms in the beginning of the decade too, but in the early nineties an ill-conceived stabilisation plan led the country to its deepest recession ever. Inflation was curbed only in 19948, as a result of the Plano Real, leading to high growth rates in 1994/95 and to a mini-cycle of investment. This growth spurt was short-lived, since the Government, fearing inflation would return and the balance of payments deficit would become unmanageable, put the brakes on the economy. For the next three years the Government fought an inglorious battle to keep its foreign exchange policy9, at the cost of holding the highest interest rates in the world (except Russia), only to devaluate in February this year. As a consequence, during 1996/98 growth rates and investment have been modest and the most recent estimates for 1999 put growth, at best, at zero level (see Table2 ).

In both countries unemployment has soared to historically unprecedented and dramatic levels and the overall public deficit (central Government and provinces/states) is proving very difficult to control (see Tables 1 and 2), though not for lack of IMF pressure. In fact, in the recent past both countries have been obliged to seek help from the IMF to overcome balance of payments problems.

Data on S&TA performed by enterprises in the two countries are limited. For Argentina GACTEC (1998) and INDEC (1998) present the results of a survey covering 1534 enterprises, of which 534 (34.8%) declared expenditures for “innovation”, but only 278 (18%) had formal structures for R&D.

“Innovation” encompasses from R&D to purchases of capital goods to be used in new products or processes. In order to focus on S&TA, we adopted a slightly more restrictive approach by including only intra-muros S&TA (R&D and non-R&D), licences and technology transfer from abroad and technical agreements with local institutions. As shown in Table 3 between 1992 and 1996 total expenditures on S&TA by the innovating firms increase by 57%, more than their sales, increasing the S&TA intensity from 1.28% of sales to 1.38%. Looking at the structure of such expenditures (ibid.) we see that the share of R&D within intra-muros expenditures and within total expenditures declines, while licenses and technical transfer expenditures increase their share substantially, as well as their intensity over sales. Imported technology expenditures were 80% higher than R&D expenditures in 1966, up from 49% higher in 1992. Reliance on local institutions, limited to begin with, declines over the period, accounting for only 8.5% of S&TA expenditures in 1996.

Such data seem to confirm the argument of the previous section: led by a growing economy, firms increased their outlays in S&TA (starting from a very low level) and, simultaneously, increased their reliance on imported technology, increased non-R&D activities (presumably, adaptations of imported technology) and reduced contacts with local research institutions. Data on technology embodied in capital goods confirm the trend towards imports. Between 1992 and 1996 new technology embodied in capital goods as the share of total investments performed by the firms remained the same (27.4%) but while in 1992 imported capital goods accounted for 43.7% of total embodied technology in 1996 this share was 53.1% (GACTEC 1998, p.129).

Innovation efforts in Argentina manufacturing industry in 1966 were aimed mainly at improving the quality of products, widen the product range and reducing labour costs. The bulk of R&D (60%) was directed to product development. The sectors in which innovation efforts are strongest are chemicals (especially pharmaceuticals and pesticides) and food industries. The latter, together with steel and non-ferrous metal products, also present the largest increase of expenditures on innovation. Those are industries which went through an important process of restructuring and growth during the nineties and grew faster during the 1992/96 period (ibid.).

The fact that sectors which present a high intensity of local natural resources and face a strong demand are the heaviest spenders on innovation fits in well with the pattern outlined above and with the behaviour of firms observed in Brazil (see below). What is at odds with the Brazilian experience is the survey finding that the intensity of innovation expenditures is inversely correlated with enterprise size and with foreign ownership of the enterprises. Given the relative size of foreign firms in Argentina the two findings may be connected. After presenting the Brazilian data we suggest a possible explanation for the difference observed in the two countries as regards the intensity of innovation efforts of foreign companies.

INDEC (1998, p.55) points out the main obstacles to innovation perceived by the enterprises interviewed. The five most important deterrents are (in decreasing order of importance): lack of appropriate sources of funding; excessive economic risk; high costs; market size and too long time for recouping the investments. Cost-related factors rank third in the list and the other four obstacles are risk-related. In other words, Argentinean firms seem to conform to the portfolio approach.

For Brazil, in the turbulent and depressed early years of the decade, evidence from sector studies suggest that firms either reduced their expenditures on innovation (mainly by cut-backs on personnel) or shifted the focus of such expenditures towards short term goals, geared mainly to cost reductions – in line with the overall defensive strategies followed during that period10. A cross-section study for 1992 (Coutinho and Ferraz 1994) shows out of 495 enterprises interviewed more than half (54%) informed that they did not invest in R&D. Those which did, intended to maintain on average the same (low) intensity of expenditures (0.7% of earnings) between 1987/89 and 1992. Although R&D intensity tended to be higher in sectors which are internationally technology-intensive (e.g. industrial automation), the most important increases in R&D/earnings ratio were observed in low-tech sectors such as cement, leather shoes and clothing.

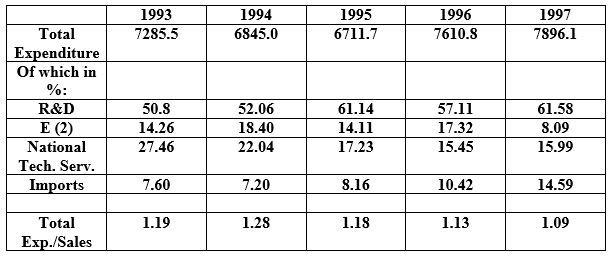

For more recent years the only available data on S&T expenditures by enterprises are collected by ANPEI (Brazilian R&D Association of Industrial Enterprises), an organisation akin to the Industrial Research Institute of the United States. ANPEI collects its data since 1992, based on a very thorough questionnaire, which firms respond to voluntarily (and often find difficult to answer). As a consequence, the number of respondents varies considerably from year to year11. Recently, Sbragia et al (1999) have analysed the evolution of a small sample of respondents over the period 1993/1997. The 86 firms which compose the sample are mostly Brazilian-owned, medium-sized or large and concentrated in the manufacture of chemical products (21%), industrial machinery (14%) and electro-electronics (12%). Therefore, the sample cannot be taken as representative of the Brazilian industry. Nonetheless, the data presented by the authors present some interesting features.

As shown in Table 4 the intensity of R&D&E (research, development and non-routine engineering) over the period 1993/97 increases in 1994 (1.28% of earnings), when economic and political conditions were very favourable and then steadily decline, to 1.09% of earnings (below the 1993 level). As expected, the share of expenditures accounted for by technology acquired abroad practically doubles over the period. The brightest feature is given by the share of R&D in total expenditures which increases from 1993/94 to 1995/97 from 50 to about 60%. Although this may be due to changes in data classification12, the increase of the share of R&D, which partially falsifies our hypothesis, requires further research.

A comparison with GACTEC data for 1996, arguing that Brazilian firms spent more on R&D in absolute and relative terms13 is tempting but should be viewed with extreme caution given the nature of the two samples as regards sectors and firm size.14

Quadros et al. (1999) have recently analysed the results of a wide-scale study done in the State of São Paulo by Fundação SEADE, the agency of the State in charge of producing statistics. The survey covered 41 193 enterprises and the authors show that 24.8% of such firms introduced product and/or process innovations during the years 1994/96, a share substantially lower than the share of innovative firms reported by GACTEC (1998), although methodological differences between the two studies inspire great caution in such comparison. Quadros et al. report that innovations are positively correlated with technology-intensiveness of the sector of activity of the enterprise, size of the enterprise and foreign-ownership (i.e. the latter tend to introduce more innovations than Brazilian-owned firms).

The same authors study the intensity of technological efforts of firms with more than 99 employees by using the number of graduate employees engaged in R&D activities. 8905 persons are employed by the 3422 firms studied – a low average of 2.6 persons per firm. The intensity of effort (the share of graduate R&D staff in total employment) is 1.2% on average. Such intensity is higher in sectors of medium technological opportunities, such as specialised equipment suppliers and scale-intensive sectors (motor vehicle and metal products), which is consistent with the pattern of competitiveness of the Brazilian industry. Since foreign-owned firms tend to dominate the more technology-intensive sectors, the two factors tend to be co-related. Intensity is higher in foreign-controlled firms, except in sectors producing machinery (electrical and mechanical) and electronics equipment for telecom. Both sectors bear out the past purchase policies of State enterprises, which exerted pressure on their suppliers to increase their local technological activities.

Using the same indicator used by Quadros et al. for Argentina, we find that GACTEC (1988 p.29) reports that engineers accounted for 20.3% of the R&D staff of 455 firms which declared they had invested in R&D in 1996. Applying this ratio to the R&D staff of the wider universe of 534 firms, it yields an average of 1.8 engineers per firm and an intensity (R&D engineers/ total employment) of 0.62% – roughly half that of the State of São Paulo.

As mentioned, the findings of Quadros et al. on the influence of capital ownership on the introduction of innovations and the intensity of innovation efforts stand in contrast with GACTEC (1998) observations. A possible explanation, which deserves further research, may lie in the restructuring of foreign companies in the region following the MERCOSUL. It is possible that many of such firms have concentrated their technological activities for the region in Brazil, the largest of the two markets (and where fiscal incentives started earlier and are more significant).

According to Quadros et al. the firms in the State of São Paulo aim their innovation efforts mainly at product quality improvement and production costs reductions – a pattern observed across the size spectrum. Consistent with this finding, their main sources of information are either customers or materials suppliers, followed by competitors. However, for large firms (500 or more employees) the internal R&D Department is the second most important source of information, preceded only by clients. Other local institutions such as consulting firms, universities and research institutes play a minor role in providing information for innovation, as do publications and patents. In Argentina suppliers and customers are two of the most important sources too but the internal R&D appears to be the main source of information. Similarly to Brazil, other components of the NSI (universities, research institutes, etc) play a negligible role as sources of information (INDEC 1988,p 54).

In other words, the study of the sources of information for innovation points to the importance of the productive chain (user-supplier relationships). From this point of view, the disruption of such changes caused by import liberalisation, leading to the replacement of local suppliers by imports, may be detrimental to local innovative efforts. On the other hand, increasing exports may act in the opposite sense, providing more advanced sources of information. Needless to say, such effects vary considerably between sectors, according to their foreign trade content.

If one includes capital goods purchases within innovation efforts (as GACTEC 1998 does), they dwarf all other types of expenditures (ibid. p.129). Such inclusion is partly justifiable on the ground that they may be complementary assets. Since the investments recently made in Argentina and Brazil seem to consist mainly of limited expansions of capacity, by the addition of new pieces of equipment coupled to changes in the organisation of production (with the outstanding exception of the motor vehicle industry), this pattern of investment is consistent with the incremental S&TA performed. The history of enterprises in Argentina and in Brazil show that, given the limited scope of their innovation activities, it is only when firms introduce major changes in their productive capacity that they introduce more radical process and product transformations. The innovation capabilities which underlie the new products and processes tend to be developed abroad. In other words: while in more technologically dynamic economies the development of innovation leads to investment, in countries such as Argentina and Brazil it is investment which brings along innovation, but mainly the use of innovation, not its local development.

Local technological development occurs when growth is combined with local specific conditions. This is a feature presented by many industries which are natural resources-intensive, as already mentioned, but it may happen in other industries too. This is illustrated by the motor vehicle industry, recently studied by Quadros and his colleagues. As reported by the press (Gazeta Mercantil 26/8/1999) during the nineties 22 new vehicles families or platforms were introduced in Brazil, as opposed to seven during the eighties. The Brazilian vehicle market presents several differences as regards the more advanced countries: roads are like Swiss cheese – a bit of road around pot-holes, alcohol is used as combustible and poorly distributed income (coupled to fiscal provisions) stimulate the use of 1.0 litre engines. Although research remains concentrated in the Northern hemisphere, Brazilian subsidiaries of TNC have developed substantial technical competence in suspension and engine design. Specific market conditions lead to the development of specific technological assets. Such assets are then used to service other markets in which the same conditions apply – adaptation of models for the Argentinean, Mexican, Venezuelan and South-African markets are performed in Brazil.

Turning to output indicators, patent data provide a similar picture. In Argentina patenting was very limited during the early nineties, largely because of problems at the Patent Bureau (an average of 608 patents per year only). In the two ensuing years the bottleneck was overcome and patents averaged 2780 per year. However, in the final two years (1995/96) the flow abated and patenting averaged 1397 patents per year. The latter figure is 77% of the average yearly patenting of the eighties and less than 40% of the seventies (GACTEC 1997). Moreover the share of non-resident patent holders increased from 70% in the eighties to 80% of total patents in the present decade (ibid.). Patents obtained in Argentina during the period 1992/96 by firms which had some R&D in 1966 totalled 320 only. Such firms obtained 88 patents abroad during the same period.

In Brazil the yearly average during the period 1990/95 (2572 patents per year) is 82% of the average for the period 1985/89. The share of non-residents is constant and overwhelming: 85% of total patents (Maldonado, 1998). Looking more closely at the patents granted to Brazilian residents, the same author shows that a considerable share of patents goes to individuals. The number of patents received by national private enterprises is very limited, never exceeding 174 in the selected years examined. Resident foreign-owned private firms play a diminutive and declining role, similarly to State enterprises. In the sample of 86 innovative firms studied by Sbraggia et al. (1999) during the 1993/97 period the number of patents obtained per firm is also very small and declining – from 1.7 per company per year to 1.1 (according to the authors, companies studied by IRI obtain, on average 130 patents per company per year).

Patenting abroad is also very limited: GACTEC(1997) reports that the European Patent Office received 34 patent requests from Argentina and 127 from Brazil over the period 1991/1993. Requests presented to the U.S. Patent Office over the years 1990/93 totalled 230 from Argentina and 570 from Brazil (ibid.). Using patent data for the period 1990/96 to study technological co-operation, Maldonado (1998) found 572 cases in which there was more than one enterprise holding the patent. Brazilian firms were present in 48 of such cases, but joint-holding between Brazilian and foreign-owned firms was found in three cases only.

Let us recall that the reform of the legislation on intellectual property was included in the ten main recommendations of the Washington Consensus. Both countries duly obliged and eliminated administrative controls of technology contracts (which aimed at, among other objectives, to restrict abusive clauses such as export prohibitions) and passed new legislation in accordance with TRIPS. In fact, Barbosa (1999) argues that the Brazilian new law is “ultra-TRIPS” in its protection to (foreign) innovators.

Since the new industrial property law have come into effect in 1966 in Brazil and in Argentina is not being applied yet (the grace period will last for five years), it is too early to assess their effects on local innovation, but it seems that the change in controls, coupled to the stimuli to import technology and (in Brazil) the change in the fiscal treatment of technology payments abroad (see below) led to a upsurge in such remittances, contributing thus to the balance of payments difficulties. In Brazil remittances rose from US$ 180 million on average for the period 1990/92 to US$ 990 million in 1996. Since such stupendous growth is not proportionate to the evolution of S&TA in the country, it is possible that the main effect of liberalisation was to open a new channel for remittances rather than stimulating the import of technology . In Argentina remittances started the nineties from a very high level (US$ 420 millions), but declined and then increased again, to reach in 1998 the same level of 1991.

Accepting the authorities’ estimates of enterprises expenditures15 for S&TA and comparing it with technology remittances, the ratio in 1996 would be 1 for Argentina and 2.8 for Brazil, suggesting that in the latter country local content of total S&TA is higher than in the former. Although this seems consistent with other indicators previously analysed it must be stressed that the estimates of the Brazilian Ministry of Science and Technology for enterprises’ expenditures are the result of complex imputations and are not very reliable.

Does it pay to be innovative in such peculiar contexts? GACTEC (1998) gives (not surprisingly) a affirmative answer by showing that the sales of the 534 innovative firms increased by 45% over the period 1992/96, in comparison with 35% increase in the total sample studied (1534 firms). Moreover society benefited from a smaller employment reduction in the first group (2%) than in the second (6%). In Brazil, for the 86 enterprises studied by Sbragia et al. (1999) the firms increased their revenue from new products from 40% in 1993 to 46% in 1997. Cost savings resulting from process improvements show a opposite trend: they decline from 7.5% of gross profit in 1993 to 0.5% in 199716. Sbragia et al. (1998) divide a wider sample of 247 innovative firms into two groups: “more” or “less” innovative according to the share of yearly sales generated by products introduced in the last five years17. Similarly to GAGTEC, they show that from 1995 to 1996 the gross earnings of the “more” innovative firms increased substantially more than the other group: while in the first case sales increased 18% in the second group they fell by 13%. However, the difference in profitability between the two groups is not statistically significant.

Since the evolution of sales is highly dependent on sectors further analysis is clearly needed. Moreover, it is possible that the causation posed by the studies who want to show that “to be innovative pays” is the reverse. Firms which had more resources available because they were selling more may have found profitable to increase their limited outlays on innovation in order to improve further product quality and to reduce costs, leading to a moderately virtuous circle. Again, further research is needed.

Exports of technology provide another partial answer. In Argentina such revenues are minimal – for the whole period 1990/98 they total US$ 56 millions. In Brazil they increase from U$$ 156 million in 1990 to US$ 474 million in 1996. Throughout the 1990/96 period over 90% of such exports are produced by “specialised technical services”, probably deriving from enterprises doing infrastructure works abroad and from Petrobras foreign operations. In both cases exports are a consequence of technological assets developed with the internal market in view and then used abroad.

Therefore it seems fair to conclude that growth and the structural reforms in Argentina and Brazil have not brought about a significant increase in S&TA performed locally by private enterprises, but they did increase the expenditures on imported technology. Historically weak links with other local technical and scientific institutions, so as to build up a “national system of innovation”, have become even weaker. Local innovation efforts aim mainly at product quality improvement and cost reductions, meritorious objectives no doubt but scarcely the stuff out of which substantial development comes. Major changes in technology seem to occur only when there are discontinuities in capacity investment, i.e. the routines of technological development, in the limited share of enterprises which have them, are geared to incremental change, not to Schumpeterian transformation of productive structures.

Some could argue that the pursuit of such incremental trajectories develop technical capabilities which then could be used for more radical innovations. This argument assumes that there is a continuum of skills which goes from small adaptations to R&D. Technical realities do not seem to conform to such view – no matter how integrated R&D has become with production, the division of labour still prevails and skills are different. The same applies to facilities, equipment, etc. Routines in a firm which does R&D systematically are very different from routines geared to incremental change. In short, the assets required for a higher ceiling of S&TA are different and require investments to be developed. As we argued above, the macroeconomic environment is detrimental to such change in the technology investment portfolio. Import liberalisation has probably increased the pace of introduction of new processes and products, raising the floor of technology investments but, by its timing, has increased the uncertainty about the revenue flow deriving from more ambitious technological investment, as discussed previously.

So far we concentrated on private enterprises but the structural reforms of the nineties have affected the S&TA of other important actors.

Historically, State enterprises were among the main investors in science and technology in Brazil. It is estimated that by the late eighties the R&D centres of Petrobras (oil) (CENPES), Eletrobras (electricity) (CEPEL) and Telebras (telecommunications) (CPQD) accounted for 10% of country’s total expenditure on S&T (Erber and Amaral 1995). In 1997 the 86 companies studied by Sbragia et al. (1999) spent, on average, US$ 7.9 million per enterprise. In the same year, the budgets of CENPES, CEPEL and CPQD were, respectively, US$ 202, 44 and 115 million – another scale of operation. The three Centres had important contributions to their record – e.g. deep water oil exploration, oil recovery and refining; energy conservation; switching technology and products (ibid.) It is estimated that CENPES research programmes to optimise offshore technology have brought benefits of about US$ 1 billion (Botelho 1999). Over the years such centres had built close links with universities and research institutes, demanding services which involved more than the simple tests commissioned by private enterprises18. Moreover State enterprises exerted a strong influence on the technological upgrading of local suppliers of equipment, machinery and other inputs. In the three Centres, especially in CENPES and CPQD, achieving greater technological autonomy was an important motivation.

Privatisation in Brazil begun with manufacturing industry, especially petrochemical and steel, purchased by local groups. In the first case this process led to the abandonment of the research centre of Petroquisa (Petrobras’ petrochemical subsidiary) which was projected to provide a qualitative change in the level of technological activities performed in that industry (Erber 1997) and to a drastic reduction of CENPES petrochemical research, intra-muros and in co-operation with the privatised firms. The latter do not seem to have increased their very limited local S&TA. In steel, the privatised companies are investing considerable sums for technological upgrading of their products and process modernisation, often linked to environment protection requirements, with support of the National Bank of Economic and Social Development. Although the monopoly of Petrobras was eliminated, the company was not privatised and the core activities of its research centre, related to the oil sector, were not harmed.

The pattern of technological activities followed by the privatised manufacturing companies seems to be determined by market requirements – in steel there was an urgent need to upgrade products and processes and to adapt them to more stringent pollution controls. The same applies to the most technology-intensive privatised firm, Embraer, a producer of medium-range jet airplanes. Building on the technical capabilities developed during its period of State-ownership, Embraer earned in 1998 about US1.5 billion, of which 90% were exports and is planning to invest US$ 850 millions in the development of new airplanes (Gazeta Mercantil, 12/8/1999).

As regards the utilities, which have been mostly acquired by foreign companies, the Telecommunications Law states that a fund for technological development should be created, but this remains, so far, a pious intention, due to the resistance of the new owners of the companies. CPQD, the R&D centre of Telebras became a non-profit private foundation and Anatel (the telecomm regulatory agency) obliged the privatised companies to provide for its budget for a three-year period (starting in 1998). According to Cassiolato et al. (1999) the Centre has changed its “product mix” against research and towards technological services. Moreover, suppliers of telecommunication equipment have decreased R&D expenditures and, within a smaller investment, increased the share of activities with a lower innovative intensity (ibid.) CEPEL (Eletrobras R&D centre) is also facing a cut in resources, since some of its main supporters were acquired by foreign firms, which can rely on the laboratories of their parent companies19 and its role and funding in the new institutional context seems uncertain. Some of the subsidiaries of Eletrobras also have important R&D centres of their own20. Since the privatisation of electric sector is still incomplete, it is too early to assess its consequences for local suppliers.

In three sectors new regulatory agencies were created: oil, telecomm and electric power. The legislation and commitment of the agencies to local technological development varies in the same order. The most important result is the creation by ANP (the oil agency) of a sector programme for R&D based on the revenue of oil royalties. This programme will be managed by MCT (Ministry of Science and Technology) with the technical support of ANP and it is estimated that it will provide R$ 340 million for S&TA over the next four years.

The consequences of privatisation for local S&TA vary then according to sectors and to the conditions prevailing during the most recent period of State-ownership. Where, as in manufacturing, State ownership was impeding investment (the State would not invest directly and did not allow the companies to increase their indebtedness), privatisation has allowed the companies to develop their S&TA according to market requirements. For the utilities privatisation will probably lead to a reduction of spending in R&D, but this could be partially offset if the regulatory agencies follow the lead of ANP.

In Argentina a few state corporations such as Petroquimica Bahia Blanca, YPF, SEGBA and Hidronor had small R&D programmes, on a much smaller scale than their Brazilian counterparts. Although not much is known about what happened to them, at least in the first case the outlook was glum because of the technological strategy of the TNC which acquired its control (Lopez 1997). The most significant case in terms of R&D, training, operation of highly complex technical facilities. and relationship with suppliers was that of CNEA (Atomic Energy Commission). CNEA was “favoured in terms of public endowments, due to its own trajectory and performance, as well as the national consensus on its strategic character partially related to military considerations. Its main liability are its sunk costs in a technology that is now put in question on a global level. After the separation of most energy-producing facilities, its budget and personnel were considerably reduced; by 1997 it employed only 500 researchers.” (Chudnovsky et al. p.11). Local technological development is not included in the priorities of the regulatory agencies in Argentina.

History then comes again to the fore. The impact of privatisation on S&TA in Brazil is much greater than in Argentina because in the former S&TA performed by State enterprises was much more important, both for the enterprises and for the rest of the national system of innovation.

As mentioned above, some of the structural reforms, especially the intertwined State and fiscal reforms, remain incomplete in the two countries. The worsening of the external accounts has added urgency to such reforms, since the IMF is exerting its well-known pressure towards a reduction of the overall public deficit. The incompleteness of the reforms cannot be ascribed to lack of technical proposals but rather to the complexity of interests which have to be taken into account, not least the relationship between regional and central Governments.

In both countries the bulk of graduate education rests in the hands of public universities. Federal universities play a more important role in Argentina than in Brazil, where the universities of the State of São Paulo are very important. Although the Federal Research Councils have institutes associated to them which perform basic research, in Argentina the role of such institutes is much greater than in Brazil, where most research is performed by the public universities. In Argentina the Secretary of Science and Technology (SECYT) is nominally part of the Ministry of Education while in Brazil Science & Technology and Education are separate ministries. Maintenance of the Federal universities is entrusted to the latter.

Most analysts agree that investment in basic research and education is a field fraught with market failures, making State intervention acceptable. In Argentina such intervention is all the more necessary given the disruption of the system of education and research caused by the military regime. In Brazil, at the same time it led to exile many prominent scientists (including the present President of the Republic), the military regime undertook the establishment of the system of graduate education and research. This type of system takes a long time to mature, but with the debt crisis of the eighties the process was interrupted and, since then, has followed a trajectory of stop-and-go, where stops are more frequent than goes. It is worth stressing that the conditions South of the Equator are totally different from those prevailing North, where the system of research and education is fully established and State intervention may be incremental – in countries such as Argentina and Brazil the problem is to establish a system. However, the World Bank doctrine of the early nineties focused investment in human capital on primary and secondary education, leaving universities and research institutes outside the pail.

In Brazil the Ministry of Education has indeed given top priority to primary education and has curbed the growth of Federal universities. The freezing of university salaries since 1995( as part of the fiscal policy for the sake of containment of expenditures) coupled to the reduction of funds for research led to a long strike of Federal universities in 1998, which ended up with a modest salary increase, leaving both parts dissatisfied. The relationship between universities and the Government is presently becoming even more adversary because of the proposals of the Ministry of Education for university autonomy, in the context of the reform of the State (the other main reform which remains incomplete). At the same time the National Research Council has adopted measures which curtail the growth of the number of researchers.

In Argentina, where salaries at the universities are among the lowest in the world, an incentive to full time professors who are also researchers was given since 1995.

It is hazardous to establish a direct connection between the financial conditions of the universities/research institutes and scientific production, but it is interesting to notice that Argentina increased the number of articles published in international journals more than Brazil21. Nonetheless, the two countries are marginal to international science – in 1995 Brazil accounted for 0.6% of the world articles in sciences and engineering and Argentina for 0.4% (GACTEC 1998).

Although the overall fiscal pattern is similar for both Federal Governments, the specific fiscal policies for S&T are different. In Argentina, as shown by GACTEC(1998), expenditures by the Federal Government (excluding Universities) increased from an average of US$ 388 millions during 1990/92 to US$ 560 millions during 1995/97. For the same two periods, expenditures by State universities increased from US$ 181 million to US$ 363 millions. Expenditures during the nineties were considerably higher than in the previous decade22. In Brazil, after reaching a peak in the late eighties (US$ 3.4 billion in 1988)23, Federal Government expenditures for S&T fall drastically until 1992 (US$ 1.6 billion), recover in the next two years (peaking at US$ 2.47 billions in 1994) and then slides down again, albeit slowly, reaching US$ 2.31 billions in 1997 (MCT/CNPq 1997). Such vagaries cannot be ascribed to overall fiscal problems only, since total Federal Government expenditures increased from US$ 111 billions in 1988 to US$ 384 billions in 1997. As a consequence, the share of S&T in total Federal expenditures fell from 3.1% in 1988 to 0.6% in 1997 (ibid.), a good indicator of the priority attached to such activities.

Notwithstanding the different trends, which point out to divergent commitments, the difference in the volume of expenditures by the Federal Governments remain very large, a shown by the figures above.

The same pattern emerges from the analysis of fiscal incentives24. In Argentina a fiscal incentive to technological activities (included in the Law 23.877 but not applied) based on rebates of income tax was put into force in 1998. The amount devoted to the tax credit in Argentina was limited to U$S 20 million for each fiscal year 1998 and 1999. Fiscal credit certificates have a validity of three years and there are maximums that can be used in each year, according to taxable income of the beneficiary. Fiscal credits can be applied to basic and applied research, pre-competitive research, technological adaptation and improvements. Excluded are administrative expenditures, energy and communications, real estate acquisition or rental, and depreciation of equipment used in the projects. In 1988 and 1999 bids were opened to firms interested in benefiting from such incentives.

In Brazil the story is more complex. In 1988, 17 years after the first proposal to establish fiscal incentives for S&T was put to the Finance Ministry, a Law providing such incentives was approved. In 1990 the S&T incentives were abrogated, together with many others. In 1991, to substitute for the Informatics Policy (an anathema to the Washington Consensus25), special fiscal incentives were given to electronics firms which complied with some local production requisites and performed S&TAs in the country, part of which had to be contracted out to universities and research institutes (Law 8248/91). Such incentives are due to expire in October this year and, so far, the Finance Ministry has shown little enthusiasm to extend them.

In the same year, as part of the liberalisation movement, Law 8343 was passed, eliminating fiscal restrictions on remittances from subsidiaries to parent companies abroad to pay for imports of technology26 and in 1994 an Executive decree eliminated a tax on remittances which still existed. As mentioned above remittances have then soared.

In 1993 the fiscal incentives of 1988 were re-established (Law 8661/93). Such incentives consist of a deduction of the income tax up to a limit of 8% of the income tax due; exemption of VAT on equipment for S&TA, accelerated depreciation of equipment and intangible assets used for such activities and reductions in the payment of taxes for technology imports if such imports are coupled to local S&T (the latter incentive was nullified by the changes mentioned in the previous paragraph). Enterprises wishing to benefit from the incentives must present a five-year plan. All S&TA are covered by the Law – from R&D to absorption of imported technology and the income tax reduction is the most sought after incentive.

However, at the end of 1997 in the aftermath of the Asian crisis, the Government introduced a new fiscal package in which the incentives for S&T of Law 8661 were cut by half and merged with other incentives which are more important to enterprises (providing food to employees). For all practical purposes, such S&T incentives have lost significance. It is worth mentioning that the Informatics fiscal incentives accounted for 2.8% of the total fiscal incentives given by the Federal Government (0.05% of the GDP) and the incentives of Law 8661 for 0.9% of the total incentives (0.02% of GDP) (MCT/FINEP 1998) – i.e. their extinction has little bearing on the fiscal equilibrium of the country.

Similarly to budget outlays, the volume of resources involved in fiscal incentives to S&T in the two countries is substantially different: while in Argentina the incentives were limited to US$ 20 millions, in Brazil the amount estimated for the general S&T fiscal incentives (Law 8661) for the 1998 budget (before the cuts) was US$ 142 millions (MCT/FINEP 1998).

A possible explanation for such divergent fiscal trajectories may be found in the political economy of budgeting. A Ministry (or Secretary, as in Argentina) of Science and Technology represents a specific and small constituency (the academic community) and a wider but diffuse group (enterprises interested in performing S&TAs). The former may be vocal but holds little power, few connections in Congress and often faces considerable prejudice against it within the Government bureaucracy, which sees it as idlers. The latter is limited, as shown above, and often has more pressing claims to pose to the financial and economic authorities (e.g. other taxes, credit conditions, protection against imports).

Given this background a Ministry/Secretary of S&T is poorly protected against the financial Ministries when the latter go on a rampage, cutting expenditures where they can. Under such conditions, the political connections of the Minister/Secretary play a very important role in protecting its fiscal instruments. In fact, the great spurt of S&T expenditures in Brazil during the period 1985/88 is largely the result of the Ministry being held by important politicians belonging to main faction of the dominant party. During the nineties the Minister was always a scientist. This may have gratified the scientific community but has certainly hindered the fiscal fight since the Minister had no political connections and was, in practice, expendable.

As a complement to such conjectures, SECYT seems to have done a much better job in explaining to society the importance of its actions, by publishing two well-cared rolling Plans for S&T 1998-2000 and 1999-2001 (GACTEC 1997, 1998), in which the difficulties of reaching the target of investing 1% of the GDP in S&T are carefully stated. In Brazil no such document can be found. Its most approximate counterpart, the Indicators of Science and Technology 1990/96 may, in fact be counterproductive, since it presents, by virtue of many imputations, a rather rosy picture of Brazilian S&TA, synthesised by the evolution of the share of GDP spent on S&T, which grows from 0.84% in 1992 to 1.22 % in 1996, with private enterprise funds rising 234% in the same period. In the foreword to the statistics it was confidently stated that the target of 1.5% of GDP for S&T would be achieved by 1999 (MCT 1997). It is a familiar dilemma for sector office holders facing the jaws of the financial ministries: one has to show that one’s job is being well done, but at the same time, no sign can be given that success is so great that it renders unnecessary increases in the resources available, or worse, that cuts can be made. Although both SECYT and MCT provide optimistic data on the evolution of S&TA in their countries, MCT seems to have overdone its Argentinean counterpart, at the cost of drastically reducing its credibility.

So far we have dealt with the fiscal issues at the Federal Government level, but a brief mention is necessary to mention the fiscal crisis at the level of the provinces/states. In Argentina GACTEC (1998) makes it clear that “the fundamental deficit as regards the Public Sector lies in scarce resources the provinces and the City of Buenos Aires allocate to this fundamental activity for the social and economic development” (p.39) – the provinces share of the public sector S&T expenditures was 5.3% in the period 1996/98. In Brazil, in the wake of the Constitution reform of 1988, most of the States passed legislation earmarking a percentage of fiscal earnings to S&T (varying from 1 to 3%) and set up institutions to manage such resources, patterned upon the very successful example of the Foundation for Research Support of the State of São Paulo (FAPESP), established in 1962. With the cold wind of fiscal problems blowing all those buds have withered – to give an example, in 1998 the Foundation of the State of Rio de Janeiro received only a tenth of what was due to it according to the law. In some States, such as Maranhão, the Foundation was simply extinguished. Only FAPESP thrives – in good measure because the law establishes that its share of the fiscal earnings goes directly to its coffers, without passing through the hands of the Finance Secretary of the State27. Its budget in 1996 was US$ 136 millions, to which should be added US$ 580 million from the State of São Paulo budget, making the State a considerable force in the development of Brazilian S&TA.

It is worth mentioning that when regional interests can be marshalled in favour of S&T expenditures some important results can be achieved. The creation of the oil R&D fund by ANP previously mentioned was due to the mobilisation of several political forces from the State of Rio de Janeiro, which accounts for 70% of oil production and where Petrobras has more R&D linkages. Additional political support was acquired by stipulating that 40% of the resources of the fund had to go the North and NE regions.

Notwithstanding the progress made by SECYT in Argentina the question remains whether setting up a system which produces science is at all relevant for the reform growth strategy. In some fields where local specificities are strong and knowledge cannot be imported, such as natural resources and tropical diseases28, such efforts are clearly necessary, but the pattern of technological development previously described suggests that “science” tends to be relegated to the highest and most unnecessary levels of the superstructure – a luxury which the market does not produce neither requires.

Again, this is not new. The insulation of scientific activities from the productive structure was a feature of the import-substitution model frequently pointed out and deprecated in both countries. The setting up of the system of research and graduate education was based on the expectation of policy-makers of the seventies that local industry would eventually need it. Present macroeconomic policy-makers do not seem to hold a similar expectation (or wishful thinking).

To conclude, I wish to share a nagging doubt: to what extent the supply of graduate students emerging from the education system is really needed by the productive sector (except for the well-paid MBAs which work strenuously in the financial sector)? Or is the graduate education level a new device for, at the same time, to retard the entry in the job market of a large contingent of the elite’s youth and to establish a new filter for access to the better-paid jobs?

3.(sic) STPs : Objectives, Instruments, Results

The broad objectives of the STP in the two countries are the same: to increase national scientific and technological capabilities, to contribute to ecologically sustainable development and to promote social and economic development, including reducing regional differences. The main novelty, as compared with the past, is the commitment to improve environmental conditions, to which several specific programmes are allotted29. As we shall see below the similarities go deeper.

As argued in the preceding section, the institutional reforms play a very important role in determining the rationale of the actors the S&TP is trying to influence. Moreover there are many S&TA performed directly by institutions which belong to other Ministries than the MOST or performed by private actors which are influenced by the other Ministries (e.g. Agriculture, Education).Therefore we begin by examining the mechanisms of co-ordination between the S&TP and the other policies.

In the two countries the highest echelon of S&TP is composed by a Council (GACTEC in Argentina and CCT in Brazil). In Argentina the Council is chaired by the Head of the Ministers Cabinet and in Brazil by no less than the President of the Republic. The Finance Minister as well as most sector Ministers (Education, Health, Defence, Foreign Affairs, Environment) have a seat in the Council. Given the distinct organisation of the State in Argentina, where the number of full-fledged Ministers is much lower than in Brazil, there are less Government representatives in GACTEC. In Brazil distinguished members of the civil society hold a seat in the Council by virtue of their scientific and technological knowledge.30

The high level of authorities present in the Council should, in theory, ensure that policy co-ordination and implementation should follow. Alas, it does not work. Simply to co-ordinate the agendas of many Ministers is an unyielding task, moreover if the subject is not regarded by the Chairman as top priority. To solve this governance problem a second layer was introduced in Argentina (an Executive Committee) where Government officers are of the level of under-secretary for specific affairs (industry, agriculture, etc), with the conspicuous absence of budget authorities. In Brazil, where the plenum of CCT has met only twice since 1994, for a session once every beginning of Presidential term, the Council was broken down into three committees. However, such committees have very broad (and vague) mandates.

In other words, in both countries there is no operative mechanism for co-ordination of S&TP with macroeconomic and sector polices. Moreover, no matter how important the contribution of representatives of civil society is for increasing policy content and legitimacy, their presence tends to worsen governance because they tend to inhibit frank discussions of problems between Government officers. The Argentinean solution to this dilemma – members of the civil society are play an advisory role to GACTEC but are not fully fledged members of the Council – is better than the Brazilian way.

Assuming that plenary sessions of the Council will be few and formal, governance of the system may be improved by establishing “functional” committees, which would bring together ministries to discuss specific issues in which all hold a stake, such as budgeting, environment control, etc. In Argentina one of such committees was created, to co-ordinate the non-university S&T public institutions (GACTEC 1998) but more are needed. In Brazil during the seventies, when STP was placed within the Planning Ministry (which is responsible for preparing the national budget) and there were national plans for S&T, budgeting was the main instrument of co-ordination. The remnants of the system can be observed in the availability of detailed information about Federal institutions spending on S&T, an instrument which seems to be less developed in Argentina.

Since S&TA are “horizontal” activities, in the sense that they are present in many sector Ministries, it could be argued that the ideal location of such function would be within the structure of the Ministry of Economics (or Planning, in Brazil). The political economy of budgeting contradicts this technocratic solution. As argued above the organised interests behind S&TA are politically weak. In contexts where the Ministry of Economics is always under pressure to cut down expenditures of other Ministries, reducing its own budget has a strong political pay-off and limited political costs. A separate Ministry for S&T provides a specific locus of defence of S&TA. Moreover, a full-fledged S&T Minister can always take its case for more resources or against cuts (against the Minister of Economics) to the President of the Republic, the ultimate authority in deciding budget allocations. Quite obviously, the stronger the S&T Minister is politically, strongest will be his/her capability to ensure a good portion of the budget for S&TA. This argument suggests that the Brazilian MCT is better placed, institutionally, than the Argentinean SST.

The morphology of SECYT and MCT share strong similarities: both have attached a Research Council (CONICET and CNPq) which finances science and performs research through institutes; and a financial agency (AGENCIA and FINEP) which directs its funds to technological activities. In Brazil there are also research institutes which are connected to MCT directly. The division of labour between CNPq and FINEP along science/technology lines dates from the nineties. Prior to that FINEP was an important source of funds for scientific institutions. The specialisation of agencies reflects in part the lack of connections of between scientific and technological activities in the two countries.

An organisation such as the Research Councils to fund scientific activities is a feature observed urbi et orbi and there is a consensus that it fulfils a function the market does not do properly. In both countries the funding of graduate education is shared with special organisations of the Ministry of Education. External evaluation of graduate courses has been an important feature of science policy in Brazil since the seventies. Such evaluation includes teaching and research facilities and the research and publication performance of the institutions and has important implications for the funds they receive in the future, as well as their prestige within the academic community. In Argentina the setting up of evaluation procedures started much later, in 1995, reflecting the different evolution of the graduate education system in the two countries.