The Brazilian development in the nineties – myths, circles, and structures

Fabio S. Erber, Nova Economia, Belo Horizonte 12 (1), pp.11-37, janeiro-junho de 2002

O artigo argumenta que as teorias de desenvolvimento econômico são metáforas que têm um forte conteúdo mítico, embora este não seja normalmente reconhecido. As políticas que derivam destas teorias têm duas agendas: uma agenda “positiva”, que especifica quais problemas são relevantes e as formas aceitáveis de resolvê-los; e uma agenda “negativa”, que contém as questões e políticas que devem ser evitadas. Esta abordagem é usada para interpretar a visão hegemônica do desenvolvimento, tal como explicitada no Consenso de Washington, mostrando que esta visão contém todos os ingredientes de um mito milenarista – o da travessia do Deserto rumo à Terra Prometida. Analisa a seguir a aplicação das duas agendas desta visão de desenvolvimento ao caso brasileiro durante a segunda metade dos anos noventa. Finalmente, o artigo discute visões alternativas de desenvolvimento, argumentando a favor de metáforas abertas, como o mito de Ulisses.

Comme la tête tranchée d ́Orphée,

la mythologie continue à chanter,

même aprés l’heure de sa mort,

même à travers l’éloignement.1

1. Introduction

Over the past years, watching the Brazilian policy-makers stick to their course in spite of all warnings about the high risks entailed by the strategy they were following, I was often reminded of Polonius’ remark about Hamlet: “if this madness be, there is method in it”. This essay is about the “method” – their view of development. The strategy is a consequence of such a view. Quite obviously, the view of development provides only a partial explanation of the strategy; other important factors, such as economic and political interests, play important roles in the definition of a development strategy. Nonetheless, such other factors are not discussed below, except in terms of the roles economic actors are supposed to play in the strategy.

Development strategies are derived from “problem-setting” metaphors. Such metaphors lead to a “positive” agenda – problems which must be tackled – and a “negative” agenda – issues which must be avoided.

For reasons that are explained at some length below, I believe the strategy followed in Brazil – as well as in most developing countries – has strong mythical contents which the article tries to bring to the fore. Such contents help to explain the “positive” and “negative” agendas of the strategy, and thereby why the strategy has failed to achieve some of its most important objectives. Moreover, they help to explain the rigid adherence of policy-makers to a prescribed path.

Analytically, my hopes are that, by focusing on that hidden aspect of development, I am contributing to a multi-disciplinary debate which may lead to the creation of “cognitive metaphors” – metaphors which may “enable us to see aspects of reality that the metaphor’s production helps to constitute” (Black 1993, p. 38).

In the following section, I briefly describe the conditions of the Brazilian society at the end of the eighties, which made it ripe for radical changes but, at the same time, posed a great uncertainty about the course to be followed.

Section 3 presents, first, a digression on problem setting and the role of myths in dealing with uncertainty faced at times of deep changes, and then it argues that the development strategy which was (and still is) hegemonic in Brazil has the same structure, the same view of the process of change and the same approach to history as the myth of “crossing the desert”. As a myth, it claims to be the result of a “universal convergence” of scientists and it holds a very restricted view of the “world” that has to be changed, which is limited to the institutional structure. It has its doctrine and initiates. In short, it is a closed-end metaphor.

Section 4 presents the “positive” agenda of the Brazilian policy-makers – its scope (institutional reform), actors and the three virtuous circles which were envisaged to produce growth. The evidence presented argues that although some of the envisaged results did come true, the virtuous circles turned into vicious circles.

Section 5 is an analysis of silence – the issues policy-makers refused to confront (their “negative” agenda) and of some implications of such agenda. The poor record of the strategy can be also ascribed to the “negative” agenda – especially its denials of the role played by the productive structure in the process of development and the role played by the state in changing the productive structure.

In the last section, I briefly review the debate about the reversibility of the reforms, but its gist lies in the argument that, contrary to what is currently stated, there are alternative views of development, such as the evolutionary approach, which sees development arising from the coevolution of productive and institutional structures. Such approach embodies uncertainty and history but, most importantly, it stresses theoretical humility, flexibility, and innovation. Therefore, it requires open-ended metaphors, which are not provided by cosmological myths such as the myth of crossing the desert.

2. A time of darkness

At the end of the eighties, Brazil was ripe for important changes. The long process of restoring democracy was ending: a new constitution was voted in 1988 and the first direct election for president since 1960 was scheduled for the end of 1989. But, defeating many hopes, democracy did not bring along economic prosperity. Quite the contrary, the economy was plagued by slow growth and inflation. The latter had been carried from “high and chronic” levels to the brink of hyperinflation, where indexing mechanisms played perverse roles. The short and sharp cycles of economic activity during the eighties –coupled with the incapacity of the governments (authoritarian and democratic) to kill the “dragon of inflation”2 and to negotiate the external debt – led to a deep disillusionment with the pattern of development which prevailed since the thirties, in which the state played a leading role (Castro, 1993).

The debacle of the Plano Cruzado at the end of 1986 (a “Plan which must succeed” and which promised an easy way out of inflation and the quick resumption of growth) was probably a watershed in the perception of agents about the possibilities of development of Brazil. It was no longer possible to sustain the idea that development was Brazil’s manifest destiny3 and the “convention of growth” which had ruled the country through military and democratic regimes (Castro, 1993) came asunder. It is significant that, in the 1989 election, there were no leading candidates upholding the previous pattern of development – and much less so the outgoing government.

International conditions favored drastic changes, too. The criticism of the import-substitution industrialization, which had mounted during the seventies (e. g. Krueger, 1974), coalesced with the reform wave of the Thatcher/Reagan period and became a blueprint for stabilization and growth of developing countries – the “Washington Consensus” (Williamson, 1990), to which we return in the next section. Such recommendations came at a time in which the capitalist world economy showed increased vigor in terms of trade, investment, and technological development, increasing the legitimacy of such recommendations.

3. Where do we go to? To cross the desert

The electoral campaign of 1989 showed that there was a consensus that deep changes were necessary in Brazil, but it also showed that the options presented by the two leading contestants were far from clear (Conti, 1999). Uncertainty was the hallmark of the period.

Economists of Keynesian and evolutionary persuasions have long argued that uncertainty is not synonymous with incomplete information, that economic agents breach the gulf of substantive uncertainty by recourse to institutions, conventions, and emotions, such as Keynes’s “animal spirits” and Schumpeter’s “entrepreneurship”.

Part of the conventions which help social actors to deal with uncertainty are “stories” told about change – of how change is necessary and, especially feasible, even under difficult circumstances. In fact, in his analysis of metaphors, Johnson (1987) argued that moving from one point to the other along a “path” is one of the basic image schemata we use. Coupled to the “scale” schemata which organizes our experience of “more” and “different” (ibid), the “path” schemata provides a basic experience of development. But to serve as guidelines for action in complex situations, such a schemata must be organized and enriched by more complex metaphors.

As pointed out by Schön (1993), we think about social problems “in terms of certain pervasive, tacit generative metaphors” (p. 139, emphasis added), which are used for problem-setting, “to describe what is wrong with the present situation in such a way as to set the direction for its future transformation” (p. 147).

Some of such tacit and pervasive metaphors are provided by myths. The function of the myth is to reveal models, reducing uncertainty (Eliade, 1963). “Myths guarantee to Man that what he is preparing to do was previously done, they help him to chase the doubts he could hold about the result of his enterprise”(Ibid, p. 173, his emphasis, my translation). Although they may have lost their sacred meaning, some myths are metaphors which are widely shared in a society – they provide “stories” about change that everybody knows.

Consider, for instance, the millenialist myth we all know. A People is immersed in sin and it is leading a miserable life under the rule of the Daemon. A courageous Leader guided by the Doctrine given by a Deity comes, and with the help of a devoted band of early followers, defeats the Daemon and leads the People to a Promised Land. However, before reaching this wondrous place, they must surmount many obstacles. Some of the obstacles are external (e. g. a desert), others are internal (doubts). Doubters must be convinced to continue by the combination of menaces and promises. Many of the persons who started the journey will not end it: either because of weakness or because they have backtracked and became allies of the Daemon. The latter must be eliminated ruthlessly. Faith and Perseverance are essential. Finally, the People reach the Promised Land. History – and the story – end here.

A characteristic of myths is that they have many variations.4 Readers of a Judeo-Christian culture will probably have recognized the story as that presented in the Exodus chapter of the Bible. However, Romans acquainted with Virgil could have recognized in the story several elements of the Aeneid. More modern versions of this myth can be found in some Marxist-Leninist visions of history: Try replacing the People by the Proletariat, the Leader by the Party, the Daemon by Capitalists and the Promised Land by Communism. As for individuals, all initiation rites (from those performed in Amerindian cultures to those necessary to be admitted to academic or esoteric communities) share some of the structural features of this myth (Johnson’s schemata): the path from a “bad” to a “good” situation is fraught with sacrifices and helped by a superior force.

A myth is no ordinary story – ancient people distinguished between “myths” (true stories) and “fables” (false stories) (Eliade, 1963). To be a “true” story, it had to be told by someone holding special powers, a priest or a chaman. Nowadays, such sacred role is performed by scientists. If a version of the myth is presented under scientific language the original sacredness of the myth is restored5 and its power reinforced. An integral part of a mythical thinking is the initiates’ belief that they hold the Truth. Skeptics, who point out that the myth may reveal only part of reality, are not tolerated. At best, they are misguided and must be enlightened, but if they persist in their doubts, this is a clear sign of being allies of the Daemon.

By the end of the eighties the Washington Consensus presented all elements needed for a modern generative millenialist metaphor. To societies plagued by slow growth and high inflation, the Washington Consensus identified the Daemon, the cause of their afflictions: the State. The State suffocated the market through protection, regulation, public property, fiscal profligacy and an ever-increasing and self-serving bureaucracy. Misallocation of resources, slow productivity growth, consumer’s damnation through high prices and poor quality products and services were the results.

The path to a new society was provided by institutional reform. Such reform, to be effective, had to be pervasive. As examined in detail by Eliade (1963), cosmological myths hold that the New World cannot come into being unless the Old World has been destroyed. For the Washington Consensus, the “world” is equated to institutions, reversing the “old” emphasis on productive structure posed by ECLA and other developmentalists. If the latter, by and large, ignored institutions, the reformers of the Consensus dealt with institutions only – the blindness of one is the vision of the other. Therefore, not only the “world” must be renewed, but the whole concept of what is the “world” is changed.

Refraining to call such sweeping reforms a “revolution” is probably a result of the socialist overtone the latter concept acquired. Nonetheless, the term adopted, “structural reforms”, has a deep resonance in Latin America, where during the sixties it was a rallying cry for change and development. It is true that, in the past, “structural reform” was a banner of the left, and now it had changed hands, but such rhetorical appropriations are not uncommon.

Although the sequencing of the reforms admitted variations, at the end of the path would lie a society ruled by efficiency and merit. As all national societies followed the prescribed path and became market-driven and democratic, history would come to an end. If duly propitiated, foreign capital and international institutions would be the presiding angels which would help underdeveloped societies to reach the desired goal, bringing guidance and manna – finance and technology.

Several rhetorical elements reinforced the story told by the Consensus. First, its claim to scientism. As it is well known, the Consensus is based on a theoretical tripod: conventional neo-classical economics, public choice theory, and the new institutional economics. The latter two may be viewed as resulting from the “invasion” of political science and sociology by neo-classical economics assumptions such as methodological individualism. Reviewing the Consensus at the beginning of the nineties, its godfather argued that “most of the universal convergence… is drawn from that body of robust empirical generalizations that form the core of economics” (Williamson, 1993, p. 1333). To conclude, he states “I regard [the Washington Consensus] as an attempt to summarize the common core of wisdom embraced by all serious economists” (ibid, p. 1334). In other words, there is one and only one Doctrine and those who disagree are apostates (or cranks).

Second, its claim to universality. As shown by the first quote above, by the early nineties the Washington Consensus – thus baptized because it reflected a list of “economic reforms that were being urged on Latin American countries by the powers-that-be in Washington” (as explained by Williamson himself – ibid, p. 1329) – had become a “universal convergence”.6 The downfall of socialist regimes, and consequently of the socialist myth as a competitor to the Consensus, strengthened this claim further. The Hegelian view of history provided by Fukuyama (1989), whereby countries which combined political democracy and market-led economies had completed their trajectory, reaching a “post-historical” condition, provided a powerful metaphor for the claim to universality. Opposition to “universal trends” is both illegitimate and inefficient.

Last but not least, doubts about the persistence and relevance of mythical rhetoric can perhaps be dispelled by noting the emphasis of reformists on the “fundamentals” of the economy7 and recalling that the Washington Consensus is presented as a Decalogue (Williamson, 1990 and 1993).

It is true that the magic of the Consensus was short-lived, at least in Washington: by the end of the decade it was disowned by its institutional parents – its policies were dubbed “hardly complete and often misleading” by no less than the Senior Vice-President and Chief Economist of the World Bank (Stiglitz, 1998, p. 1).

Nonetheless, the Consensus marches on, with variations. Stiglitz has left the Bank and the latter’s bureaucracy now speaks of “second generation” reforms, i. e. the Consensus was correct but incomplete. Although there are alternative views of development, such as provided by the evolutionary research program, which regards development as resulting from the coevolution of institutional and productive structures, they have not reached policy-making echelons.8 Moreover, there is no sign of recanting in the Brazilian policy-making team. Ideas sometimes take a long time to cross the Equator line.

4. Uses of the myth: the positive agenda – virtuous and vicious circles

Few politicians in the Brazilian history have presented such messianic traits to the public as Fernando Collor, the winner of the 1989 election. Not with standing the fact that he had run a millionaire campaign and been favored by the media and bourgeoisie, probably his victory was also the result that the electorate fell less insecure with a white, handsome, educated, rich, and very determinate candidate than with a former worker – a testimony to the uncertainty previously mentioned and to the importance of the mythical Leader.9

Collor set the country along the reform path predicated by the Washington Consensus. Although he had to resign the Presidency in 1992 following corruption charges, the path was trod on by his successors – Collor’s Vice-President, Itamar Franco and the latter’s Finance Minister, Fernando Henrique Cardoso, who was elected in 1994 and reelected in 1998. It is on the latter’s development strategy that we concentrate on.

The Consensus, as a truly generative metaphor, sets a “positive agenda”, the issues to which policy should be addressed to, and a “negative agenda”, the issues which should be avoided. Such agendas were wholeheartedly embraced by Cardoso’s policy-makers. In this section, we analyze the positive agenda and in the next section, the negative agenda.

The positive agenda was ambitious. Its foremost objective was to defeat the inflation dragon and then to keep it under control. The stabilization plan10 was based on fiscal measures to bring public deficit under control and on an ingenuous monetary reform, which first introduced an account currency to align prices and then transformed this currency into money proper. In subsequent stages, inflation was kept under control by a combination of foreign exchange and monetary anchors – an overvalued exchange rate (superimposed on import liberalization) and very high interest rates. Introduced in 1993, when Cardoso was the Finance Minister, the successful stabilization led to his subsequent election (1994) and reelection (1998) as President, indicating the degree to which the population abhorred the dragon.11

Nonetheless, the positive agenda did not stop at price stabilization. It aimed also at growth, by laying down “sound macroeconomic fundamentals” and establishing three virtuous circles of higher investment, higher productivity, and higher growth, described below. Moreover, at a deeper level, policy-makers intended to transform what was seen as an “organic” (corporative) fabric of relationships into a more individualistic society – a truly liberal intention.12

In practical terms, this has been equated to establishing market-friendly institutions, following the Consensus Decalogue – e. g. by privatizing state-owned enterprises and setting up sectoral regulatory agencies; eliminating differences between local and foreign-owned enterprises; eliminating price controls by the state and establishing a regulatory system to avoid market power misuse; liberalizing foreign trade and investment; establishing a new legislation for intellectual property which strengthens the rights of innovators;13 liberalizing labor legislation and fostering regional Integration under the MERCOSUR.

Three entwined virtuous circles would arise from such reforms, leading to higher investment and growth.14 The first and most important circle was related to globalization (defined as trade and investment growth above production growth and elimination of distinctions between foreign and national capitals). Trade and foreign direct investment (FDI) would introduce competitive pressure into the erstwhile protected markets and bring in more modern machinery and inputs, increasing productivity. Trade and FDI are closely related: FDI requires freedom to import but it has, at the same time, a greater propensity to export. In the long run, such investment would lead to increases in productivity and hence to greater exports. It did not matter that a considerable part of FDI was directed to purchasing local (private and state-owned) firms, since this was a prelude to increases in productivity and greater exports. Therefore, the large deficit in the transactions account of the balance of payments was a temporary phenomenon as was the reliance on short-term international finance to fill in the foreign exchange gap. By the same token, the very high interest rates required to attract financial capital would be short-lived. Moreover, financial liberalization would allow firms to access cheaper international sources, reducing the impact of the high internal interest rates. The first virtuous circle and, in fact, the whole strategy were predicated upon the availability of cheap, long-term foreign finance.

The second circle was related to stability: the end of inflation had brought about a positive income redistribution, favoring those which had suffered most under the dragon’s flames and thus increasing the internal market. At the same time, stability allowed for longer time frame, so that the entrepreneurs would be stimulated to invest and consumers to buy, fuelling the market.

Trade liberalization would further stability by acting as a brake on price domestic producers. Privatization and deregulation would coalesce with imports and FDI to increase competition. Wider markets, positive expectations, and greater competition would lead to new investment and trade liberalization would allow imports of new vintages of machinery and inputs and therefore to increased productivity, exports and growth. Fiscal reform would support a decline in interest rates and more “flexible” labor legislation would reduce costs and increase international competitiveness. The adoption of an over-valued exchange rate strengthened the mechanisms of the two circles, linking further the stabilization and growth components of the strategy.

Finally, ancillary to the two previously described circles, regional integration would increase trade and FDI and, at the same time, widen the national market.

From such virtuous circles, different roles for social actors are derived – as in Orwell’s farm, some are more equal than others and the former lead the process. In the virtuous circles, the state – shorn of its enterprises and committed to fiscal equilibrium – moves to the backstage and foreign enterprises – acting as investors, traders, and financiers – play the leading roles. To such demiurges of development, all propitiatory incentives were given: from changing the Constitution to nominally equalize them with national enterprises to fiscal and credit incentives in order to attract them. National enterprises play the supporting roles – as one would expect from reading President Cardoso’s (1964, 1971) academic works.15 Difficult roles, it should be said, given the import liberalization, the overvalued exchange rate, and the very high internal interest rates, especially for those enterprises which had limited access to the international market. To the many who failed to cross the desert, social Darwinism was the answer.

Faith and Perseverance were not lacking among policy-makers: despite the Mexican, Asian and Russian crises, they adhered to the prescribed path, with some detours such as shifting the weight on foreign actors from financial capital to direct investment. The most important change came in early 1999 in the wake of a foreign exchange crisis, when policy-makers (after using up a considerable part of foreign exchange reserves) were obliged to overhaul the foreign exchange policy16 and adopted “inflation targeting”, under the “prudent supervision” of the International Monetary Fund. Although those are important tactical changes, the reform strategy is maintained. Therefore, it is worthwhile to briefly analyze the performance of the virtuous circles.17

Some expectations of the virtuous circles were fulfilled. First, inflation was kept under control: from a staggering 5,154% yearly rate in June 1994, just before the launching of last phase of the Real Plan, it declined to 1.7% in 1998. Although the drastic overhaul of the foreign exchange policy in the beginning of 1999 pushed the inflation rate up to 9%, this was much less than all analysts (including the government’s) had expected. Second, FDI did come in: from US$ 2 billion in 1994, it grew to about US$ 30 billion in 1999/2000. Third, productivity also increased – labor productivity in industry increased by close to 6% per year between 1991 and 1998.18 Fourth, with the end of inflation, urban labor real average earnings19 increased by 8.7% between 1994 and 1995, leading to a consumer expenditure boom.

Nonetheless, virtue was not duly rewarded. Gross Domestic Product growth rates changed from fair in 1994 (5.9%) to modest in 1995 (4.2%), mediocre in 1996 and 1997 (2.8% and 3.7%), and finally to nil (or close to) in 1998 and 1999 (0.8%). Investment measured at current prices was low in 1994 (20.8% of GDP) and declined to 19.1% in 1998. Unemployment rose to unprecedented levels,20 and informal employment now accounts for more than half of the total – features which partly explain increased productivity.

Labor earnings continued to grow up to 1997, albeit at a slower pace, but then declined in 1998 and 1999, when they stood at the same level as that of 1995. The combination of unemployment, reduced earnings, and tight and expensive credit led to a drop of consumer expenditures.21

Such poor performance can be ascribed to another circle – of vicious nature. The envisaged virtuous circles engendered a perverse progeny: vicious circles in which the stabilization anchors (over-valued exchange rate and high interest rates) led, on the one hand, to growing deficits in current transactions, increasing foreign capital requirements, and thus preventing any decline in interest rates. On the other hand, the latter led to low investment and unemployment as well as to growing fiscal deficits, which sustain high interest rates. In other words, the development strategy faces two entwined constraints: foreign exchange and fiscal restrictions.

It is worth showing a few figures to illustrate such constraints. Exports grew by 17% between 1994 and 1998, but imports soared ahead, increasing by 77% in the same period. As a consequence, the current account deficit was 4.5% of GDP in 1998.22 The high internal interest rates fuelled a drive to indebtedness abroad and the ratio of net debt/yearly exports grew from 3.5 in 1990 to 4.5 in 1999. Servicing this debt takes a toll – in 1999, payments for interest and amortization accounted for 71.5% of exports and were equivalent to more than double the entry of FDI (Kleber, 2000). In other words, the foreign front is structurally vulnerable – a point to which we will return in the next section.

Pushing interest rates to sky-high levels to attract foreign finance capital and keep inflation under control seriously damaged public accounts too. Although the government (all spheres) has managed to maintain a surplus on the primary account by cutting down expenses and increasing fiscal revenue by several ad-hoc measures, payment of interests has produced burgeoning deficits, which reached more than 10% of GDP in 1999. 23 By the end of that year, the net public debt was equivalent to 48% of GDP (Gazeta Mercantil, 24/1/2000). The poor quality of public services underlies such figures, which most deeply hurts the more underprivileged groups of society. Since Brazil presents one of the world’s most unequal income and wealth distribution, this means that it is the bulk of the population which bears the brunt.

The turn of the century was heralded as a new age. In fact, building upon idle capacity and lower interest rates – which enabled increases in the sales of durable consumer goods – and with foreign reserves bolstered by an IMF “package” during a period of relative calm in the international financial markets, GNP growth rate shot back to 4.2 % in 2000, inflation was kept within the targeted limits (6%), and open unemployment was slightly reduced – to 7.1%. As a consequence of the reduction of interest rates, public deficit was cut down to 4.5% of GNP. Government officials, supported by a highly sympathetic media, boasted that a new growth cycle had started – the promised land was on sight.

By the second quarter of 2001, such optimism was substantially reduced. The Argentinean crisis led to another sharp devaluation of the real and the Central Bank inflected its previous policies of lowering interest rates, in order to keep inflation within its targeted limits. Moreover, the lack of investment in electric power generation and transmission, due to an ill-conceived privatization scheme, produced a severe rationing of energy. As a consequence, uncertainty has increased considerably and investment plans are being revised downwards. We are still plodding through the desert.

To conclude this section, let us consider an important part of the positive agenda which has remained largely unfulfilled – the reform of the state. The government has provided the economic team with a considerable degree of “bureaucratic insulation” and adopted several important measures as regards state intervention in the economy, such as the privatization of state-owned companies and the setting up of regulatory agencies, as previously mentioned.

Nonetheless, some of the most crucial state aspects in Brazil remain untouched. The Constitution of 1988 had still wet ink on its pages and fiscal experts all around the country proclaimed that its fiscal structure was unmanageable. Since then, projects of fiscal reform have piled up in Congress. It was supposed that a thorough fiscal reform would be one of the priorities of the government, since fiscal “soundness” is an acknowledged “fundamental”. This was not so! In spite of having an overwhelming majority in Congress, which has approved all major projects of the executive, the latter has shown no interest in presenting a coherent fiscal reform and the debate on the subject recently progressed only under IMF pressure. Other aspects of the state reform, such as electoral legislation, 24 distribution of power between the country’s states and even the administrative reform were also neglected.

It is probable that this important aspect of the reform’s positive agenda was curtailed by political realities: to reform the state in Brazil implies discussing the regional distribution of power, income and wealth, built along decades. The present government was elected by a coalition which brought together the President’s party, nominally a social-democrat party, and a conservative party which has been in power since decades, benefiting from all the advantages laid by the ancien régime. Although the latter has recently and vigorously adopted the liberal rhetoric, it is essentially a practitioner of the realpolitik with high stakes put on the status quo of the state. To breach the issues related to the state reform means opening a Pandora box or, more simply, a can of worms.

As evolutionary economists are fond of saying, “history matters”. After fifty years of deep involvement in direct promotion of the country’s development, it is not easy for the state to move backstage. As growth sputtered political pressures to step up, state intervention mounted. Throughout the Cardoso period, a conflict has divided the economic team, hinged upon the degree of state intervention which was necessary in industrial and trade policy (ITP). 25

Since all members of the team are economists and many of them were previously academics, a substantial part of the debate was couched in terms of economic theory.

The establishment and operation of the virtuous circles was fully entrusted to market mechanisms enhanced by the state reform. If ITP had a role, it would be found in the eventual failure of such mechanisms.

But the very abundance of market failures poses a strategic problem: by which failure should ITP begin. Welfare theory does not provide an answer to that question, since there is no a priori Paretian criterion to distinguish between two imperfect positions when there are several market failures and it is impossible to remove all failures simultaneously (Nath, 1969). External criteria deriving from other economic and political considerations must be introduced to select priorities, as Lall (1994) argued was done in Southeast Asia.

Against this, the faction opposing any ITP has argued that market failures have to be balanced against failures introduced by the very action of the state. Unfortunately, once again, theory and empirical evidence prevent straightforward comparisons of cost and benefits of the two types of failures and we are driven back to other, “nonscientific” (i. e. not derived from neoclassical economics) criteria.

Lacking such criteria, industrial and trade policy was conducted on an ad-hoc manner, trying to solve specific problems afflicting some sectors or activities, especially exports. Such an outcome, which may be interpreted as a partial victory of interventionists (or a vindication of history), falls short of an ITP aiming at changing the productive structure of the country. Such a shortcoming can be partially ascribed to the negative agenda shared by all policy-makers – discussed in the next section.

5. Uses of the myth: the negative agenda – productive and regional structures

As remarked above, portraying the past as “evil” or “inefficient” is a common trait of cosmological myths. Franco, a learned economic historian, goes to the length of singling out the “lost” decade of the eighties, when import substitution was irrelevant, as the prime example of the slow productivity growth ascribed to the import substitution industrialization (Franco, 1998).

Denial extends to other structural components of the previous pattern of development. Thus “autonomy of decisions” looses any positive normative sense 26 and tends to become a clear sign of old/evil thinking. As I have argued in more detail elsewhere (Erber, 1999), this had deep consequences for activities which were linked to the autonomy objective but are also important to the transformation of the productive structure, such as scientific and technological activities. National enterprises and parts of the state bureaucracy were the greatest losers of this normative reversal.

If autonomy has become a bad word, “picking the winners” is even worse – something akin to praising pork among Moses followers. This has prevented industrial and trade policy from evolving from a set of ad-hoc interventions to a fully fledged ITP, in which it is recognized that sectors play different roles as regards economic and technological development and, therefore, as regards the international comparative advantages of the economy. Recognizing that potato and computer chips are not equivalent, the least a modern government of a developing country can do is to provide a “vision” of a desired industrial and technological structure to be discussed with the private sector so as to orient investments.

No such vision can be found in Brazil. Given the role played by exports in the virtuous circles previously described, this omission is especially striking: since the eighties trade specialists have warned that Brazilian exports consisted mainly of products which tended to exhibit slow growth rates in the international market. Among such specialists, we find at least two above suspicion – Batista and Fritsch (1993) – who came to hold high posts in the Finance Ministry during Cardoso’s tenure – an indication that it is not lack of information coming from trustworthy sources which presides the silence around the productive structure.

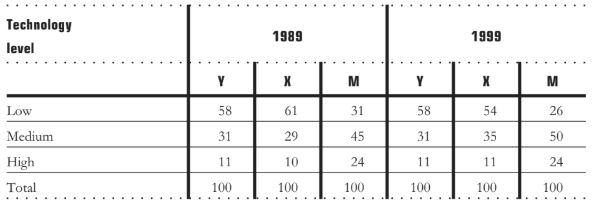

Although Brazil is a “global trader”, in the sense that it exports to many countries, and close to 60% of its exports are manufactured products, 27 such products tend to be low-tech products, either resource – or scale-intensive commodities which grow slowly and are subject to cycles on which Brazil has no control (see Tables 1 and 2). 28 Those were the sectors established during the second half of the seventies, under the last stage of import substitution (II PND). 29 High-tech, science-intensive products, which are the fast-growth sectors in the international market, 30 account only for 11 and 7% of manufactured exports, respectively. More than a third (36%) of the high-tech and two thirds of the science-intensive exports are due to one firm only – Embraer, which produces airplanes. It is somewhat ironic that this success is to a large extent due to the heavy state investments the ade in the enterprise during the import substitution, autonomy-seeking period, when the enterprise was state-owned.31

Table 1 – Structure of the Brazilian industrial production (Y); exports (X) and imports (M) according to technology level of products as a percentage of total value – 1989 and 1998

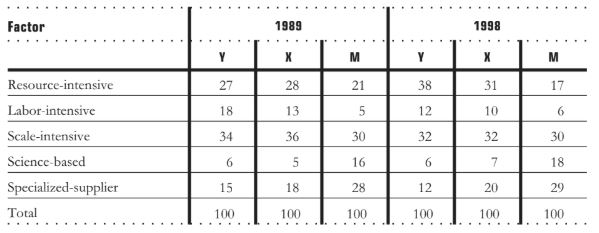

Table 2 – Structure of the Brazilian industrial production (Y); exports (X) and imports (M)

according to factor intensity of products as a percentage of total value – 1989 and 1998

Given such export structure, it is not surprising that the Brazilian exports increased by 4.6% per year during the period 1994/98, while international trade grew by 7.6% (Pinheiro et al., 1999) and that the Brazilian share of total world manufactured exports fell from 1.37% in 1980, when the projects of the II PND were coming on line, to 0.94% in 1997 (Lall, 1999). In 1999, the favorable export prospects, given by a sharp devaluation combined with a sluggish internal market, did not materialize: the quantum of manufactured exports remained stable and their value decreased by 7% (FUNCEX, 2000). Only in 2000, manufactured exports showed a better performance, surpassing the 1998 level by 10%, suggesting that it requires more than macroeconomic policies to fuel exports.

In contrast, imports are made up of medium and high-tech products, which increased their share of total manufactured imports along time (see Table 2), pointing to a structural trade balance deficit. In fact, over the period 1994/98, imports increased by 77%, as compared with an export growth of 17% only (Pinheiro et al., 1999). In the latter year, the trade deficit of electronics products accounted for 88% of the total trade deficit (ibid and Melo and Gutierrez, 1999). As expected, the 1999 devaluation led to a decline in non-oil imports, which was partly offset in 2000, as a result of imports of intermediary goods for the higher output level. As a consequence, the manufactures trade balance remained negative.

Foreign trade reflects the country’s productive structure and, as can be seen in Tables 1 and 2, the technological structure of industry has remained stable, with prevailing low-tech products. Comparing 1989 with 1998, there is a noticeable growth in the share of resource-intensive products, mostly at the expense of labor-intensive products and of specialized suppliers. The latter’s decline can be ascribed to imports of capital goods, which now account for more than 50% of the apparent consumption of such products.

It is true that important microeconomic changes underlie the relative structural stability – witness the impressive productivity increase in manufacturing industry previously mentioned, but those are infra-structural changes which do not alter the country’s international insertion. With the present productive and trade structure, the Brazilian economy is caught in a trap: any resumption of growth leads to a more than proportional increase in imports, not accompanied in the same measure by exports. The ensuing deficit in the foreign current account must be closed by foreign capitals.

It is perhaps ironic that the trap above described, which results from the different elasticities of imports and exports, in fact, is an up-dating (applied to manufactures, which provide the bulk of the Brazilian foreign trade) of the well-known diagnostic of the foreign exchange constraint posed by Prebisch in 1949 (CEPAL, 1949), which laid the ground for justifying import-substitution industrialization in Latin America.

As shown above, the foreign indebtedness of Brazil has increased the vulnerability of the economy. Reliance on financial capitals to cover a growing current account deficit would further increase the vulnerability, requiring high interest rates to cover the risks and thus reducing investments. Moreover, as the recent experience has shown, international finance capital cannot be relied upon to support long-term development prospects. Therefore, FDI should sustain the main role. The main motives of recent FDI inflows have been the Brazilian market (enlarged by the other MERCOSUR countries) and the acquisition of local enterprises (Laplane and Sarti, 1997). 32 But, in the long run, the growth of such market as well as the growth of exports are limited by the existing productive structure, reducing the prospects of a robust growth of FDI and giving rise to another vicious circle. The same constraints apply to national firms too, since the latter are more tightly bound to the local market than the transnational companies.

In other words, we argue that attention should be paid to the productive structure of the economy. Given the well-known problems of coordination and time horizon entailed in structural change, 33 to hope that the market by itself will bring about the necessary changes requires a great amount of faith. Such attention could be paid even within the present development strategy, if policy-makers were a bit more skeptic about the power of the market. The silence imposed by the negative agenda on the change of the productive structure is deafening.

Moreover, even for sectors for which there were ITPs, no vision of structure is to be found. This is best exemplified by the automotive sector, where soaring imports and competition with Argentina for FDI led the Brazilian government to set up a complex scheme of incentives, in which restrictions on imports of final products were combined with incentives to import parts and components and fiscal incentives to investment. Nobody knows whether authorities government officials considered one, two or twenty new assemblers desirable.

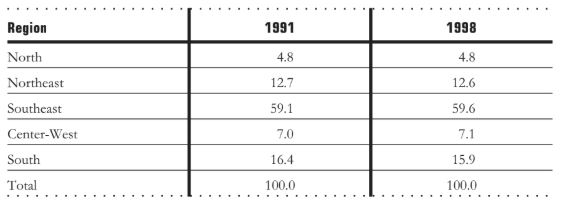

Finally, the silence imposed by the negative agenda extends to the regional structure. Brazil is a continental country plagued with striking regional differences, which have not improved during the nineties, as shown in Table 3. Although a substantial part of the public deficit is due to the regional governments (states and municipalities) the federal government, nominally committed to reduce public deficit (one of the “fundamentals”) and constitutionally bound to oversee the Union, has turned a blind eye on the savage competition between the regional levels to attract investments. The “fiscal war” certainly benefits the enterprises which use the incentives, but the benefits accruing to the communities are more doubtful, especially if one takes into account the intergenerational conflict underlying the future reduction of fiscal revenue.

Table 3 – Brazil: regional structure of the gross domestic product – in percentage – 1991 and 1998

In order to address the problems of regional development, a structural view of the spatial distribution of economic sectors is required. It is unlikely that market forces by themselves will lead to a more equitable distribution and the government, prodded by the political forces asking for more growth, commissioned a study of investment prospects along regional axes of development. Only a small share of investments would be funded by public resources, the rest depending upon private funds. The former have been included in the budget law, but it is worth recalling that the federal budget approved by the Congress is not mandatory – the Finance Ministry is at liberty to disburse the funds or not, according to its assessment of the fiscal conditions and, in the past, many projects remained at the planning board for such reasons. As discussed above, the destiny of this plan depends heavily on the outcome of the fiscal reform debate and on the possibility of reducing interest rates.

6. Conclusions

It is a consensus that for Brazil (as well as the for the rest of Latin America) the eighties were a lost decade from the point of view of development. As shown by Pinheiro et al. (1999), except for inflation (and it is a big exception) the record of the nineties as regards growth, employment, and export performance is worse. For the near future, no major change of strategy is foreseen, provided no major bad news emerge from the foreign front. 34 As indicated above, there are strong reasons to doubt about the capacity of this strategy to produce high and sustained growth rates which would lead to the reduction of unemployment. To many observers the government seems to be doomed to go on plodding through the desert.

Nonetheless, to consider the nineties simply as another lost decade is to miss the importance of the changes it introduced in the Brazilian society. Some observers may, simultaneously, recognize the importance of the changes and wish to cancel them. Other observers claim that the reforms are still incomplete and, therefore, it is sufficient to trod on the prescribed path, finishing the present wave of reforms and then moving on to the “second generation” of reforms (e. g. Pinheiro et al., 1999).

I differ from the two observations. I suggest that the former observers, placed most often in the opposition, are falling prey to another type of myth, cycle myths, in which time is reversible and a former, better world (a Golden Age) can be restored (Eliade, 1963). The “goodness” of the previous pattern of development is highly questionable – e. g. the income distribution it produced. Moreover, a trait which distinguishes primitive from modern thinking is the recognition by the latter of the irreversibility of time. Thinking about time and of social processes as irreversible is one of the cornerstones of the evolutionary theory. If this is true, the nineties produced a new institutional structure in Brazil.

As regards the latter observers, I argue that the basic assumption of the reform strategy – that institutional reform suffices to lead to development – is wrong and that their overall Weltanschaaung is reductionist and misleading.

From an evolutionary perspective, development comes from the coevolution of the institutional and productive structures. As indicated above, the reform of the productive structure must be tackled in Brazil. This will require further institutional change, since the state must intervene in the process and new governance mechanisms must be established (e. g. for coordination of state agencies and of such agencies with the private sector) as well as efficient mechanisms for financing investments out of national funds.

The coevolution of institutional and productive structures is path-dependent, laden with national specificity and it continuously poses new problems so that the past cannot be abolished and history never comes to a rest. Contrary to the perspective held by the institutional reformers, Heraclitus rules: we never plunge into the same waters twice and there is no map for the path.

Complex tasks as those involving development require open-ended metaphors to deal with them. The degree of uncertainty about development processes should lead to a substantial degree of theoretical humility. Substituting dialogue for the Doctrine is an important epistemological step which leads the development strategy to emphasize flexibility and learning. Such features are found in the evolutionary approach.

If such views are correct cosmological myths are a trap to be avoided but Odysseus, the wandering hero who uses intelligence to cross uncharted seas, 35 provides an appropriate myth to think about development.

Referências Bibliográficas

AVERBUG, A. (1999) Abertura e integração comercial do Brasil nos anos 90., In: GIAMBIAGI, F.; MOREIRA, M. (Eds.). A economia brasileira nos anos 90. Rio de Janeiro: BNDES

BATISTA, J.; FRITSCH, W. (1993) Dinâmica recente das exportações brasileiras (1979-90)., In: VELLOSO, J.; FRITSCH, W. (Eds.). A nova inserção internacional do Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: José Olympio Editora

BLACK, M. (1993) More about metaphor., In: ORTONY, A. (Ed.) Metaphor and Thought. Cambridge University Press

BONELLI, R.; GONÇALVES, R. (1998) Para onde vai a estrutura industrial brasileira?, Texto para discusso, 540, Brasília: IPEA

CALASSO, R. (1990) As núpcias de cadmo e harmonia. , São Paulo: Companhia das Letras

CARDOSO, F. (1964) Empresário industrial e desenvolvimento econômico no Brasil., São Paulo: DIFEL

CARDOSO, F. (1971) Política e desenvolvimento em sociedades dependentes., Rio de Janeiro: Zahar Editores

CASTRO, A. (1993) Renegade development: rise and demise of state-led development in Brazil., In: SMITH, W.; ACUÑA, C.; GAMARRA, E. (Eds.). Democracy, markets and structural reform in Latin America. [s.l.]: Transactions Publishers

CASTRO, L. (1999) História precoce das idéias do Plano Real., Dissertação (Mestrado) – Instituto de Economia, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro.

CEPAL. Comissión Economica para América Latina. (1949) Estúdio econômico de América Latina, 1948., Santiago: [s.n.]

CONTI. (1999) Notícias do Planalto., São Paulo: Companhia das Letras

ELIADE, M. (1963) Aspects du mythe., Paris: Editions Galimard

ERBER, F. (1999) Structural reforms and science and technology policies in Argentina and Brazil., Buenos Aires: Secretaria de Ciencia y Tecnologia

EZRAHY, Y. (1971) The political resources of American Science., Science Studies, v. 1, n. 2

FRANCO, G. (1995) O Plano Real e outros ensaios., Rio de Janeiro: Francisco Alves

___________ (1998) A inserção externa e o desenvolvimento., Revista de Economia Política, v. 18, n. 3

FUKUYAMA, F. (1989) The end of history? , [s. l.]: National Interest, summer

FUNCEX. (2000) Boletim de comércio exterior., [s. l.]: [s. n.]

HABERMAS, J. (1971) Toward a rational society., London: Heinemann Educational Books

JOHNSON, M. (1987) The body in the mind., The University of Chicago Press

KATZ, J. (1999) Cambios en la estructura y comportamiento del aparato productivo latinoamericano en los años 1990 y su relación con lo tecnologico e innovativo., Buenos Aires: Secretaria de Ciencia y Tecnologia

KERENYI, C. (1968) De l’Origine et du Fondament de la Mythologie., In: JUNG, C.; KERENYI, C. Introduction a l’Essence de la Mythologie. Paris: Payot

KLEBER, K. (2000) A dívida externa ainda dá pesadelo., Gazeta Mercantil, 24 jan

KRUEGER, A. (1974) The political economy of the rent seeking society, American Economic Review, n. 64

LALL, S (1994) The east asian miracle: does the bell toll for industrial strategy?, World Development, v. 22, n. 4

___________ (1999) Science, technology and innovation policies in east Asia: lessons for Argentina after the crisis, Buenos Aires: Secretaria de Ciencia y Tecnologia. Mimeogr.

LAPLANE, M.; SARTI, A. (1997) Investimento direto estrangeiro e a retomada do crescimento sustentado nos anos 90, Economia e Sociedade, n. 8

MELO, P.; GUTIERREZ, R. (1999) Complexo eletrônico: balança comercial em 1998, Relatório Setorial, BNDES, n. 1

MENDONÇA DE BARROS, J.; GOLDENSTEIN, L (1997) Avaliação do processo de reestruturação industrial brasileiro, Revista de Economia Política, v. 17, n. 2

MOREIRA, M. (1999) A indústria brasileira nos anos 90. O que já se pode dizer?, In: GIAMBIAGI, F.; MOREIRA, M. (Eds.). A economia brasileira nos anos 90. Rio de Janeiro: BNDES

NATH, S. (1969) A reappraisal of welfare economics., London: Routledge amd Kegan Paul

NELSON, R. (1995) Recent evolutionary theorizing about economic change., Journal of Economic Literature, v. 33, Mar

PINHEIRO, A.; GIAMBIAGI, F.; GOSTKORZEWICZ (1999) O desempenho macroeconômico do Brasil nos anos 90. , In: GIAMBIAGI, F.; MOREIRA, M. (Eds.). A economia brasileira nos anos 90. Rio de Janeiro: BNDES

SABÓIA, J.; CARVALHO, P. (1997) Produtividade na indústria brasileira: questões metodológicas e análise empírica., Texto para discussão, 504, Rio de Janeiro: IPEA

SCHÖN, D. (1993) Generative metaphor: a perspective on problem-setting in social policy., In: Ortony, A. (Ed.) Metaphor and Thought. Cambridge University Press

SILVA, A.; MEDINA, M (1999) Produto Interno Bruto por Unidades da Federação 1985-1998, Texto para discussão, 667, Brasília: IPEA

STIGLITZ, J. (1998) More instruments and broader goals: moving toward the post-washington consensus., Helsinsky: WIDER Annual Lecture

WILLIAMSON, J. (1990) Latin American adjustments: how much has happened?, Washington: Institute for International Economics

WILLIAMSON, J. (1993) Democracy and the “Washington Consensus”, World Development, v. 21, n. 8

WORLD BANK (1993) The east Asian miracle, Oxford University Press, 1993

Artigos relacionados

Parcerias Estratégicas (CGEE) v.15, 2010

Inovação Tecnológica na Indústria Brasileira no Passado Recente – uma resenha da literatura econômica

Nova Economia, Belo Horizonte 18, 2008